What is known about the origins of psoriasis?

December 9, 2015

- Related Topics:

- Autoimmune disease,

- Autism,

- Complex traits,

- Evolution

A curious adult from Germany asks:

We don’t know a lot about how psoriasis started or why it is still as common as it is. In fact, we don’t even have a good handle on what causes it!

What we do know is that it is a condition where people have patches of skin that are discolored or a different texture from the rest of their skin. We also know that it happens because their immune system attacks their skin by mistake. And importantly for the discussion here, we know that it is partly genetic.

If you have relatives who have psoriasis, you are more likely to have it too. When we see conditions running in families like that, it means that genes are probably involved.

Each gene is a little stretch of DNA that holds the information for one small part of you. We have genes that tell us the color of our hair and eyes, and genes that tell us what height we could be. And there are a bunch of genes that can make someone more likely to have psoriasis.1

Having these genes doesn’t mean that you will automatically have psoriasis. They just mean that you have a bigger chance of reacting to something that’ll end up causing the condition.

So how common are these genes? Pretty common.

It turns out that about 3% of people in the world have psoriasis!2 It might be surprising that the condition is so common since it can be uncomfortable and painful. So why is it still around?

Protection from infection?

Gene versions that cause problems usually disappear eventually due to natural selection. Because of that, these gene versions will slowly fade over time. But if it has a silver lining, the genetic difference might hang around.

Doctors and scientists think that a lot of genes related to genetic conditions may have good roles too. That’s why they are still around. So even though we may see psoriasis as a negative, the genes that cause psoriasis may also be helping us somehow.

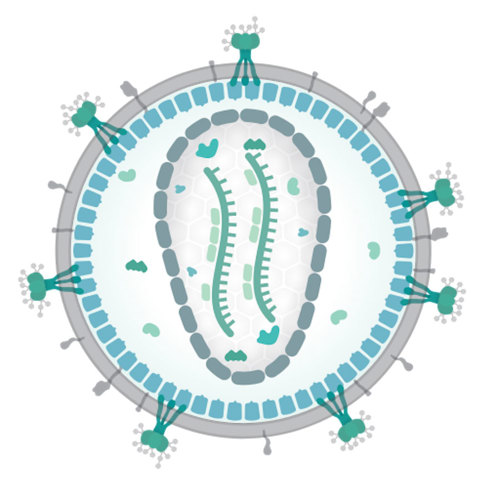

One idea is that a lot of the genes that we find in people with psoriasis are helpful in fighting HIV.3 Genes that protect people from getting AIDS are obviously an advantage. But it’s important that we keep two things in mind.

First, we know that we find the same genes in people who have psoriasis and people who are good at fighting HIV. But that doesn’t mean that the genes that cause psoriasis are the same ones that fight HIV. It may be two different genes that are right next to one another, so we see them together a lot. (Scientists say these genes are “linked.”)4

Second, we have to remember that evolution takes a long time and HIV hasn’t been in humans for very long. We may think of 100 years as forever, but evolution needs thousands of years to act.

Because of this we know that psoriasis genes aren’t still around because they keep us from getting HIV. But these same genes might protect us from another infection (maybe a relative of HIV) that has been around for much longer.

Gene changes can protect us

This appears to be the case for a gene called CCR5. People who are missing part of this gene can be completely protected against HIV. This is great today, but as we said earlier, HIV hasn’t been around very long.

It turns out that people missing this part of CCR5 are also protected against another infection called smallpox. Until it was wiped out in the 1970’s, smallpox had been infecting humans for at least 2,000 years.5 In this case it is possible that the missing part of CCR5 is around because of smallpox protection, but now it provides protection against a new infection.

It doesn’t seem like the change in CCR5 is harmful on its own (except maybe being more likely to be affected by the West Nile Virus)6 so it’s not surprising that this change would stick around. But there are examples where something that looks like it would be trouble is actually helpful.

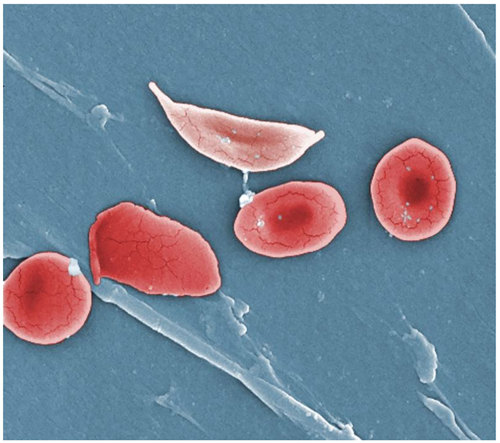

A classic example of this is sickle cell anemia. The gene version involved in this deadly genetic disorder can actually sometimes protect people from malaria.

Sickle cell anemia and malaria

Sickle cell anemia is a genetic disorder that makes people very sick. This means that they may not be able to have children, and we would expect sickle cell disease to disappear.

But sickle cell anemia is much more common than we expect. Why is that?

It turns out that having mild sickle cell disease (called sickle cell trait) protects people from malaria. This disease has been infecting humans for almost 5,000 years and for most of that time has been incredibly deadly.7

People who have mild sickle cell disease are protected from malaria. This allows them to pass on their genes as often (or maybe even more often) than people who do not have sickle cell.

This is despite the fact that they are more likely to have a child with sickle cell anemia. The protection against malaria has allowed sickle cell disease to remain in the population.

Disorders aren’t always bad

For now we don’t have anything as clear-cut as sickle cell anemia with psoriasis. With most of evolution we can never know exactly why anything happened.

We can come up with explanations, but we can never test those explanations to see if they are true. For both of the genes we talked about, sickle cell and CCR5, we know they protect us from some infections, but the reason they are still around might be something that we haven’t thought of yet.

Either way it’s important to remember that the things we call “disorders” aren’t 100% bad for us. Some of these might be protecting us from something else really harmful.

Skip Navigation

Skip Navigation