What does chimera DNA look like?

April 28, 2006

- Related Topics:

- Chimera,

- Mosaicism,

- Rare events,

- Mutation

A curious adult from California asks:

“What does chimera DNA look like? Are chimeras and mosaics the same thing? And are there any changes in chimera DNA?”

The word “chimera” comes from a creature in Greek mythology that had body parts from a goat, a lion and a serpent. We use the word today to describe the same basic idea: someone who is made up of parts from multiple individuals.

A person who is a chimera is made up of cells from different people. Some of their cells have the DNA of one person and the other cells have the DNA of another person. But how does this happen?

Imagine that inside of a womb, instead of there being only one egg, there are actually two. If both of these eggs get fertilized by two different sperm cells, you get fraternal twins. Fraternal twins are equally as related as any pair of siblings.

Now, imagine that instead of developing separately, these fertilized eggs fuse together. Then only one baby would develop. This baby would have cells from not one, but two different zygotes (or fertilized eggs).

Remember, every zygote carries its own unique set of DNA. So the baby would have two different sets of DNA — this baby would be a chimera.

Most chimeras grow up normally and look like everyone else. You probably wouldn't be able to tell that the person was a chimera. You could potentially see patchy areas on the skin or two different colored eyes, but even these are pretty subtle changes.

This may seem weird at first. Shouldn't a fusion of two people look different? Wouldn’t it have two heads or four arms or something?

The reason this isn’t the case is because the fusion of the two eggs happens very early on in development. At this point, the cells haven’t started to build body parts.

After the fusion, a given cell can't tell that its neighboring cell actually has a different set of chromosomes. They work together anyway, as if they were all created from the same zygote.

Genetic Mosaicism

Chimeras are not the only people who carry different sets of DNA in their bodies. Mosaics also have variation in their DNA from one cell to the next.

A mosaic, unlike a chimera, starts out with the same set of DNA in every single cell. You could look at any cell in the body and the DNA inside of it would be exactly the same as the DNA inside a different cell.

At some point during a mosaic’s life, though, their DNA changes in one cell. Now, the DNA in that cell is slightly different from the DNA in the neighboring cells.

This scenario is very common. In fact, technically we are all mosaics.

Our bodies are made up of trillions of cells. Most of these cells contain the exact same copy of our DNA. Over the course of our development and lives, however, the DNA in some of these cells can change.

There are many things in the environment that can change, or mutate, your DNA. The sunlight hitting your skin or chemicals in the food you eat are two examples.

Most of the time these mutations are harmless. Only occasionally do these mutations cause problems. For instance, if a mutation affects how fast a cell can grow, the cell can become cancerous.

The changes that occur due to environmental factors are usually very small and very rare. Most of the time, only one or a few cells in your body will carry any single mutation.

It is possible, though, for a mosaic to have as many as half of the cells in his body that are different from the other half, just like in a chimera. But how?

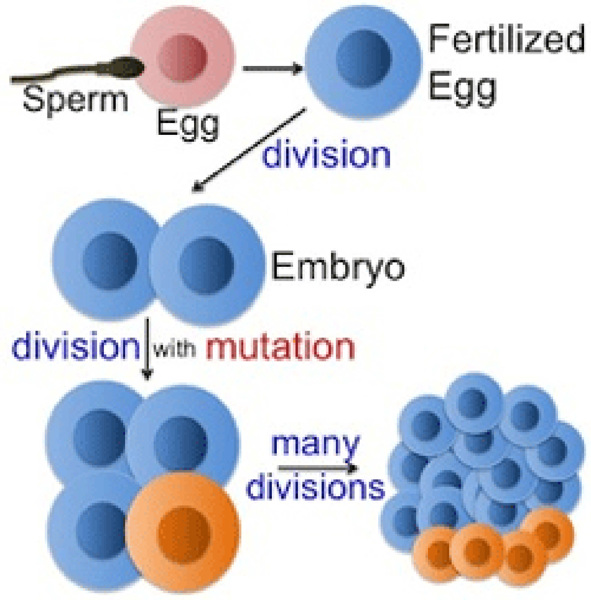

If the DNA changed very early on in development, then more cells in your body are likely to carry the mutation. Remember, we start out from a single cell. That cell divides and then each of the two new cells divide.

This happens over and over until you end up with 100 trillion cells or so. Imagine that the first cell has divided to make 2 cells.

During this division, a mistake was made and one cell ends up with a DNA mutation. Now these two cells go on to make the rest of the person. In this case, half of the person’s cells will have different DNA than what it started with.

Even with these mutations, our own cells are much more similar to each other than they are to the cells from another person. This means that if you were to compare one of your cells to a cell from your brother or sister, you would find a lot of differences. You would find far less differences if you instead compared two of your own cells to each other.

Chimeras vs. Mosaics

So chimeras have cells with vastly different DNA, like a brother or sister’s. A mosaic has cells with only small changes. Does this sound confusing? Let's use a crime scene scenario to demonstrate this difference.

Let's say Bob is accused of murder. The police have blood from the crime scene and check the DNA against some of Bob’s skin cells.

If Bob is a mosaic, most likely the DNA of two cells will be similar enough that the DNA test will show he did it. If Bob is a chimera, though, the DNA may be as different as a brother's. And DNA tests are certainly good enough to distinguish between Bob and his brother.

Therefore if Bob is a chimera, he could potentially get away with murder. (As long as the police don't look at the DNA in the same cells he left at the crime scene, anyway.)

There you have it. A chimera’s DNA is the same as anyone else’s – they just have two different kinds of DNA. Some cells have one kind, the rest have a different kind.

Author: Natalie Dye

When this answer was published in 2006, Natalie was a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Biochemistry, studying bacterial cytoskeletal proteins in Julie Theriot’s laboratory. Natalie wrote this answer while participating in the Stanford at The Tech program.

Skip Navigation

Skip Navigation