How did light skin evolve in Europe?

October 7, 2009

- Related Topics:

- Skin pigmentation,

- Human evolution,

- Pigmentation traits,

- Complex traits,

- Genetic variation,

- Ancestry

A curious adult from California asks:

"I understand that lack of sunshine led to Caucasians becoming pale because of lack of vitamin D. But how did it happen?"

This is a great question that gets at how changes can happen in a species because of the environment. Pale skin was always there in European ancestors' genes. It just took a crisis to bring them out and make most everyone there have light skin.

Get Your Sun

Given all the concern about skin cancer, it can sometimes be easy to forget that sunlight has important benefits too. For example, people need the sun to make their own vitamin D.

Nowadays we can (although we don't always) get enough of this vitamin from our multivitamins, fortified milk, fortified orange juice, etc. But thousands of years ago, we had to rely mostly on the sun.

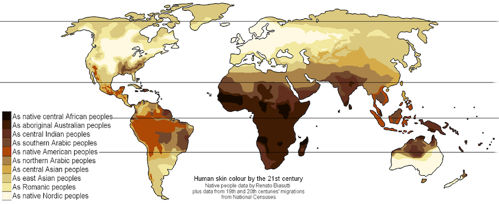

Which wasn't a problem in Africa, where we all started out. There is so much sunlight there that getting enough vitamin D wasn't the problem...the sun's harsh UV light was. Close to the equator, it's beneficial to have darker skin which helps protect you from UV damage.

But getting enough vitamin D was certainly a problem in Northern Europe. As you know if you've ever visited there, it is not a place conducive to getting a lot of sun. The winter days are short and the cold weather causes people to cover a lot of their skin and stay indoors. And it is cloudy an awful lot.

It is so hard to get enough sun under these conditions that dark skin is actually a problem. Which is probably why Northern Europeans turned from dark to pale -- to get enough vitamin D.

This explains the why pretty well but not the how. To understand the how, we need to go over a few basic genetics concepts. Then we'll see how a trait like light skin can become common.

Bringing Hidden Traits Out

As anyone who looks around knows, people all look pretty different. For the most part, these differences are there because we are all different genetically.

Now this doesn't mean we all have different genes. As humans we all share the same set of genes. What makes each of us different is that we can have different versions of these same genes.

This explains why we're all different. But it doesn't do a very good job of explaining how, for example, two darker skinned parents can have a lighter skinned child.

To understand this, we need to remember that we have two copies of each of our genes -- one from mom and one from dad. What this means is that the same person can have copies of different gene versions.

For example, there is a skin color gene called SLC24A5. This gene comes in two different versions, dark (D) and light (L).

People with two dark versions (DD) tend to be much darker than people with two light versions (LL). People with a copy of each (DL) tend to be in between.

Imagine that two DL parents have a child. The child will get one version of the SLC24A5 gene from mom and one from dad. Which copy the child gets from each parent is totally random.

So half the time mom will pass a D and half the time an L. Same with dad. This works out to each child having a 1 in 4 chance of getting two L's and so being much more light skinned than his or her parents.

Of course, the truth is even more complicated! SLC24A5 isn’t the only gene that affects skin color. Turns out there are lots of different genes involved, each of which can come in different versions.

That means a person can have an assortment of light and dark versions of different genes. And that person’s child might have a slightly different assortment, depending on what they inherit from both parents.

That is how Africans can sometimes have a lighter colored child (and, for that matter, a darker one). But now we need to figure out how light colored skin became so common. The answer lies in something called selection.

Pale Skin Sweeps Europe

Imagine a group of Africans migrates to Northern Europe. This population has lots of different gene versions. In terms of skin color, that means that there is a range of colors from dark to darker.

Most of these folks have two dark versions of the SLC24A5 gene -- they are DD genetically. But a few might also be DL. These DL people would tend to be on the lighter side of the skin color range. And the same will be true for many other genes involved in skin color: some of these folks will have lighter skin versions of these other genes.

At some point after coming to Europe, darker skinned people started getting sick. Since most of the people had dark skin, this means that most of the people were sick. This was not a good time to be European.

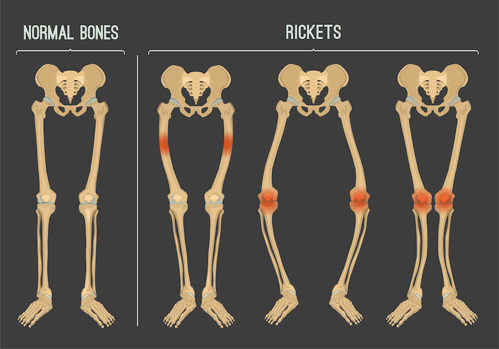

Not only were they sick, but their darker skinned children were too. The kids had weak bones and suffered many problems including an awful disease called rickets. Most of these children didn't survive to have kids of their own.

Remember, though, that there were a few lighter skinned people who were DL genetically (they had a light version of SLC24A5). They did better because they could get more vitamin D from the weak European sun. And some of the kids inherited their parents' less dark skin.

In the next generation, the people who could go on to have kids were the lighter skinned ones. What this meant was that the relatively rare DL folks could now find each other and have kids. Sometimes, both parents would pass an L and make a much lighter skinned child.

These LL people were much better adapted to their surroundings and did better than even their DL neighbors. These LL folks then went on to have kids who would mostly be light skinned. Repeat this a few times and voila, you end up with a much paler group of people.

It is important to note here that lack of sun didn't cause a genetic difference that led to lighter skin. The difference was already there in a few people. It took a pretty brutal selection to rapidly make it the most common skin color gene version in Europeans.

Odds and Ends

This is a nice, clean story. Of course nothing in genetics is so simple. There are always a few twists to keep things interesting.

For example, early results suggest that pale skin swept through Europe between 6,000 and 12,000 years ago (scientists can tell from looking at the DNA around the SLC24A5 gene). But Africans arrived there 30,000-40,000 years ago. So why did it take so long for pale skin to take hold?

One idea is diet. Pale skin swept Europe right around the time that agriculture took hold. The idea is a hunter-gatherer can get enough vitamin D from his or her diet and that a farmer can't.

These tens of thousands of years in weak sunlight may also have allowed a random change (or mutation) in the SLC24A5 gene to be passed on. In Africa, having light skin was bad for you. In hunter-gatherer Europe, it didn't much matter. So a mutation in the SLC24A5 gene might be better tolerated in Europe.

If this were the case, then the original settlers didn't have a light version of SLC24A5 when they left Africa. It could have appeared after they arrived in Europe.

Another interesting twist is that SLC24A5 isn't the only way to end up light skinned. For example, most east Asians have lighter skin, but don’t have the light-skin version of SLC24A5. Lighter skin in these populations is due to differences in entirely different genes!

Both groups were under the same pressure to become light skinned. But they responded in different ways based on the genes already within their populations.

Read More:

Author: Dr. D. Barry Starr

Barry served as The Tech Geneticist from 2002-2018. He founded Ask-a-Geneticist, answered thousands of questions submitted by people from all around the world, and oversaw and edited all articles published during his tenure. AAG is part of the Stanford at The Tech program, which brings Stanford scientists to The Tech to answer questions for this site, as well as to run science activities with visitors at The Tech Interactive in downtown San Jose.

Skip Navigation

Skip Navigation