My nephew was born with an extra chromosome. Is this genetic, and is there a name for it?

March 8, 2011

- Related Topics:

- Trisomy/Aneuploidy,

- Chromosomes,

- Meiosis,

- Translocation

A middle school teacher from Massachusetts asks:

I am very sorry to hear about your loss. Your nephew had a genetic disorder called a “trisomy.” Trisomy is the scientific term for what you described: being born with an extra chromosome.

Trisomy is a genetic condition, but it’s not the kind that’s passed down from parent to child. Trisomy can be compared to cancer, in that both result from a random mistake in a person’s genetics.

A whole range of mistakes can happen in a normal cell to cause cancer. In the case of a trisomy, a very specific mistake happens when an egg or sperm cell gets made.

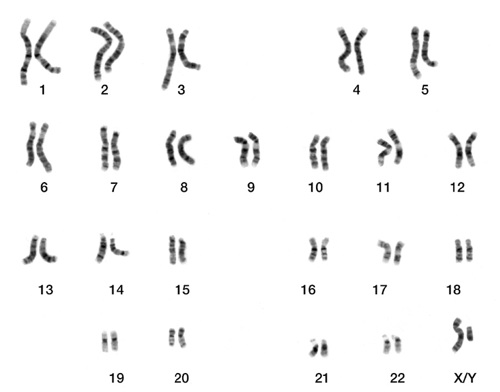

Most cells in your body have two copies of every chromosome. But an egg or sperm only has one copy of each chromosome. The number of chromosomes is split in half during a process called meiosis. When meiosis gets messed up, you can end up with too many or too few chromosomes.

One extra chromosome in an egg or sperm cell means that the resulting fertilized egg will have three copies of a chromosome, instead of two, causing a trisomy. Just like some things can increase your risk for cancer, there are risk factors for trisomy. But they aren't things that you can control.

The likelihood of a trisomy pregnancy increases with the age of the mother. And just like in the case of cancer, where certain inherited genes can increase your risk, there are some risk factors for trisomy that can be passed down from parent to child.

For example, a person can be at a higher risk of a trisomy pregnancy if they have something called a balanced translocation. Around 1 in 600 people carry a balanced translocation1, meaning that some of their egg or sperm cells carry an extra chromosome.

Balanced Translocations and Trisomy

Most of the time, chromosomes exist as individual units: they are independent of one another.

Sometimes, though, part of one chromosome gets swapped with part of another, completely different, chromosome. That’s called a translocation – when part of the genome moves to another place.

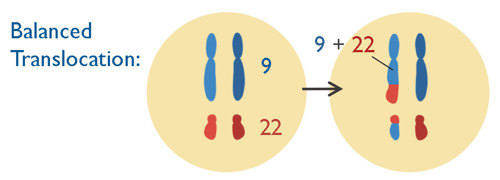

But what if it’s not just a small part of a chromosome, but most of a chromosome? For example, what if almost all of chromosome 22 switches places with a small part of chromosome 9? In this case, chromosomes 9 and 22 essentially end up “stuck together.”

This “balanced translocation” doesn’t have much of an effect on the person who carries it, because none of their genetic information gets lost or repeated. Their genes are just in a different order. But it can definitely increase his or her chances of having a child with a trisomy.

During meiosis, one copy of each chromosome is randomly passed down to a sperm or egg cell. If one of your chromosome 9s actually has most of chromosome 22 stuck to it as well, things can get hairy.

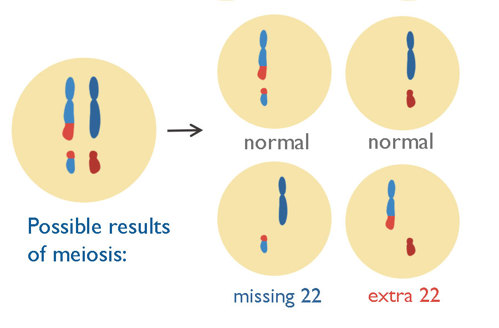

In this diagram, you can see how the chromosome numbers get messed up due to a balanced translocation. A cell with chromosomes 9 and 22 “stuck together” can make sperm or egg cells that have a normal number of chromosomes. But they might also make sperm or egg cells that are missing a chromosome, or that have an extra copy of a chromosome. The resulting fertilized egg can end up with an extra copy of chromosome 22 because in addition to inheriting two normal copies from each parent, they also inherit an “extra” copy that’s stuck to chromosome 9.

Most people don’t need to worry about a balanced translocation, since they're so rare. If someone has had a trisomy pregnancy and is worried about their risk of a second one, they should talk to their doctor or genetic counselor who can give them information based on their specific situation.

Too much of a good thing

But why does having a trisomy cause so many problems? Why do we need two, and exactly two, copies of every chromosome?

It comes down to balance. If your DNA is like a recipe for making you, then every gene is an ingredient. If you throw in too much of any ingredient, you can mess up the whole recipe. Because there are so many genes on each chromosome, having an extra chromosome can mean having too much of a lot of different “ingredients.”

Similar to when you bake cookies, the result depends on which ingredients you add. Since people have twenty-three pairs of chromosomes, there are many possible types of trisomy, which can lead to a wide range of effects.

Some people are walking around right now with an extra chromosome without knowing it. For example, having extra sex chromosomes (X or Y) doesn’t always cause significant symptoms. That means some people might never find out they have an extra sex chromosome or two. If you're making chocolate chip cookies, this would be like adding too many chocolate chips: it won’t necessarily cause problems.

Other trisomies are more likely to cause symptoms. Down Syndrome, for example, is caused by having an extra copy of chromosome 21, or Trisomy 21. While Down Syndrome leads to significant symptoms, it’s not always life-threatening.

However, these cases are generally exceptions to the rule. As you have experienced, most trisomies unfortunately end in miscarriage or premature death. It all comes down to a mistake that happens during meiosis.

Author: Elizabeth Finn

When this answer was published in 2011, Elizabeth was a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Genetics, studying epigenetics and placental development in Julie Baker’s laboratory. She wrote this answer while participating in the Stanford at The Tech program.

Skip Navigation

Skip Navigation