Can humans have an odd number of chromosomes?

May 12, 2011

- Related Topics:

- Chromosomes,

- Trisomy/Aneuploidy

A high school student from Tennessee asks:

"Can humans have an odd number of chromosomes?"

Yes – it is possible for humans to have an odd number of chromosomes. And you might be surprised by how often it happens.

In up to 20% of human pregnancies,1 the fetus may end up with an unexpected number of chromosomes. Most of these fetuses do not go on to be born, or they die shortly after birth. But some do just fine.

In fact, 0.3% of all babies born have an odd number of chromosomes.1 Sometimes, with conditions like Down or Turner syndrome, you can see the effects of the extra chromosome. Other times, the symptoms are minor or nonexistent. You or your friend sitting next to you could have an extra chromosome and you might not even know it!

What I want to do for the rest of the answer is talk about why the number of chromosomes sometimes matters and sometimes doesn't. To do that, we need to take a quick refresher course on what DNA and chromosomes are and what they do.

The Recipe for Making You

DNA is part of all living things and is like a recipe. Pine tree DNA has the recipe for making a pine tree. Dog DNA has the recipe for making a dog. And, you guessed it, your DNA has the recipe for making you.

These recipes are found in our genes, which are found in our DNA. Think of them as the list of ingredients in a recipe.

To make it simpler, let's think of DNA as the recipe for a birthday cake. When we make a cake, we first need to know which ingredients to add, and how much. The genes in DNA tell us this important information. One gene might tell us to measure out two cups of flour. Another gene might tell us to crack open three eggs and add them to the batter.

Of course, our genes don't tell us to add ingredients like flour and eggs. Instead, our genes have the list of different proteins needed to make us. Each protein, like each cake ingredient, contributes to one small part of the whole. For example, baking powder in a cake serves a purpose: it makes the cake rise. In humans, one gene tells us that we need the protein hemoglobin, which is in our blood and carries the oxygen that we breathe throughout our bodies.

Our DNA is broken up into pieces called chromosomes. It is as if we took a recipe and spread it over lots of different pages. Each page of the ingredient list is a chromosome. One chromosome, or page, might tell us how much flour and vanilla we need. Another might tell us the right amounts of sugar and salt.

Humans normally have two of each chromosome. This is because we get one of each chromosome from each of our parents. Most people have 23 pairs of chromosomes (for a total of 46). So, our recipe actually has two of each ingredient page – just like we have two copies of each chromosome.

Each copy of your chromosome pair has the same form, but they are not exactly identical. So, each page tells us roughly half of the ingredients that we need for the full birthday cake. If we need two cups of flour, one page (from our father) might tell us that we need 1.1 cups of flour. The other corresponding page (from our mother) might tell us that we need 0.9 cups.

Give or take?

Like I said, people normally have two of each chromosome, which means two of each ingredient list page. If a person has only one of a particular chromosome, they will have only one of a particular ingredient list instead of two. As a result, they will add only half of the normal amount of the ingredients on that page to the cake batter. If a person has three copies of a chromosome, they will put in too much of some ingredients.

We're now ready to see why sometimes having an odd number of chromosomes is a problem, and why other times it is perfectly fine. It has to do with how important some ingredients are to the cake. And to you and the way you function.

First, think about the most important ingredients of our cake. What would happen if we did not have two copies of the ingredient page with flour on it? If we had only one, we’d put in about half as much flour, and if we had three, we’d put in too much. In both cases, what we take out of the oven would not resemble a cake.

In almost all cases, having too many or too few of a chromosome is like having too many or too few of a page with very important ingredients on it. Most of the time an embryo with an extra or missing chromosome does not survive until birth or dies shortly thereafter. Those fetuses are missing too many important genes to survive. But this isn’t always the case.

For some cake ingredients, the amount that we add to our batter is less important. What would happen if you put in too much sugar because you had an extra ingredient page? The cake would probably taste too sweet, but we could still eat it.

So, sometimes, a person can survive with an extra chromosome, though they will have symptoms. For example, a person with Down syndrome has three copies (not two) of chromosome 21 and usually has developmental delays and intellectual disabilities. Chromosome 21 is the smallest human chromosome, with a smaller number of "ingredients" on it. This is probably why a person can survive with three of them.

And, what about too little sugar? One example of this is Turner syndrome. In Turner syndrome, a person has only one X chromosome instead of two Xs or an X and Y. This means they will have several symptoms including slowed growth and delayed onset of puberty, but otherwise they will be fine.

Finally, the exact quantities of some cake ingredients are unimportant. Think about the frosting. The frosting is my favorite part too – but if we had a little more of it, our cake would still be a cake.

The sex chromosome pages have frosting-like ingredients. So a woman who has three X chromosomes instead of two (or a man with one X and two Y chromosomes instead of one of each) has no symptoms. The last one is true even if the man has 3 or more Y chromosomes.

Here’s a table that shows some of the chromosome differences that people can have. Only a few aneuploidies (as having an extra or missing chromosome is called) are compatible with life.

|

Condition |

Karyotype |

Symptoms |

|

Down Syndrome |

47, tri21 |

Developmental delay, intellectual disability |

|

Edwards Syndrome |

47, tri18 |

Low birth weight, small jaw and mouth, intellectual disability |

|

Patau Syndrome |

47, tri13 |

Low birth weight, holoprosencephaly, polydactyly |

|

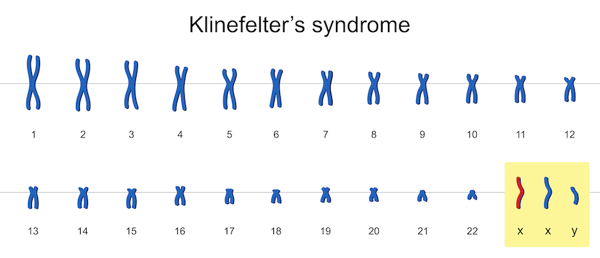

Klinefelter Syndrome |

47, XXY |

Infertility, weaker muscles, poor motor coordination |

|

Turner Syndrome |

46, XO |

Infertility, short stature, heart defects |

|

Triple X Syndrome |

47, XXX |

Increased height, mild dysmorphic features |

|

XYY Syndrome |

47, XYY |

Increased height, increased prevalence of learning disability |

|

Other sex chromosome syndromes (variable) |

48, XXYY ; 48, XXXY ; 49, XXXXY |

Variable; often include infertility and shortened lifespan |

Finally, there is one special case where there is no effect of having an odd number of chromosomes. It is called a balanced translocation, and it occurs when one chromosome, or one part of one chromosome, sticks to another one.

This is like ripping one page of the ingredient list out of our recipe book and taping it to another page instead. Sure, we'd have an odd number of pages, but all of the ingredients that we need are still listed in the correct amounts, just in a different order. This occurs in about 0.001% of people, and usually has minimal impact on daily functions.

In conclusion, humans can have an odd number of chromosomes – but the effects of having an odd number of chromosomes are varied, from being fatal to causing no effect whatsoever. The outcome depends on which chromosomes are extra or missing, and how sensitive the recipe is to changes in the amounts of "ingredients" on those chromosomes.

Author: Julie Granka

When this answer was published in 2011, Julie was a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Biology, studying inferring historical processes from genetic data in Marc Feldman’s laboratory. Julie wrote this answer while participating in the Stanford at The Tech program.

Skip Navigation

Skip Navigation