Can sons (or daughters) ‘run in the family’?

October 13, 2019

- Related Topics:

- Genetic sex,

- Sex ratio,

- Complex traits,

- X linked inheritance

Many people ask:

“My husband and I have 7 sons and no daughters. I’ve had 3 miscarriages. I’m starting to think that we just can’t have daughters. Is it possible that we have some genetic issue that causes our female embryos to die and our sons live?”

– A curious adult from New Hampshire

“I have heard — anecdotally — about some potential condition that some women may have in which they can only carry female embryos/fetuses to term. Is this an actual thing? My mother is one of three girls. I am also one of three girls. My sister is pregnant with a girl. I am also currently pregnant with a girl, but in prior pregnancies I miscarried four male embryos. I am very curious given that my husband and I are interested in having multiple children.”

– First Time Mom from NYC

You’re not the only ones—there are plenty of people from families with big gender imbalances who claim that boys or girls just “run in their family.” I’ve heard this first hand—my own extended family is almost 80% female! And as you can imagine, people have been trying to find an answer to the question of why some parents have boys, and others girls, for most of history.

There are a few genetic disorders that can lead to spontaneous miscarriage of male embryos, but they are very rare. And women who carry the DNA for those disorders typically show other symptoms.

Outside of those rare diseases, there’s no genetic reason that we know of for someone to have more boys or girls. Despite decades of research, no one has ever found a “sons” or “daughters” gene.

But what exactly do we know about whether gender runs in families? And if it’s not genes, then what can tip the gender balance?

Could it just be a coincidence?

First, let’s consider the possibility that there isn’t any underlying cause at all, and that it’s all just up to chance. This might not feel very likely, but humans are notoriously bad at telling the difference between real patterns, and simple coincidences.

Take the example of a family with 8 children, all of whom are boys. Most people would see a family like this and think that there must be a scientific reason for such a large gender imbalance.

But it’s like flipping a coin. It would be rare to get heads 8 times in a row, but certainly not impossible.

Let’s do the math. For eight children, the chance of all of them being male is:

(1/2) X (1/2) X (1/2) X (1/2) X (1/2) X (1/2) X (1/2) X (1/2)

= (1/2)8

= 1/256

That means that for every 256 families with 8 children, on average one of them will have 8 boys.

So how many families like this are there in the United States? According to a 2011 report from the New York Times, there are roughly 8,100 families who have 8 kids living at home. That means that there are probably around 32 eight-boy families in the U.S., purely due to chance!

And that report only looked at households. It doesn’t include older families whose kids have moved away from home! So 32 is an underestimate – there are probably many more eight-boy families in the U.S.

It’s important to remember just how many people exist in the country—not to mention the world! If you have enough sheer numbers, even very unlikely things are bound to happen eventually.

As an aside, I did the math with my own family, and the chances of us being 80% female come out to be 1 in 45. That’s roughly the same probability of having your flight cancelled at the airport—an event that doesn’t feel very unusual at all.

Can gender “run in the family?”

Scientists have been asking whether the proportion of males or females (also known as the sex ratio) can run in the family since at least the 1960s. And even though no one has ever found a gene that can affect the sex ratio, there’s still some debate over whether or not a gene like this might exist.

But why aren’t we sure? Like many things in science, it’s because we have conflicting evidence.

In some studies, the scientists decided that the sex ratio ran in the father’s family.1–3 But in other studies, scientists couldn’t find any evidence for gender imbalances being genetic at all.4,5

Why did these scientists get different answers to the same question? It could be because they looked at different families in a different part of the world, or because they used different statistical tests.

No one has ever been able to link specific genes to sex ratio. And even the scientists who think there is a genetic effect admit that it’s pretty small.

Plus, we know that the sex ratio can be affected by certain environmental factors, which would also be shared in a family. This makes it hard to decide if any pattern we see is because of genetics, or something else.

In short, it’s not impossible that there’s an undiscovered “daughters” or “sons” gene in your family, but the chances of that are small. It will take more research to figure out if genetics affect sex ratio at all!

Rare X-linked disorders

While it's hard to pin down an exact cause of gender imbalance in most families, there are exceptions. Some genetic disorders can lead to a higher number of daughters.

Specifically, some X-linked disorders can lead to spontaneous miscarriage of male embryos in particular. Some examples of this include large X-chromosome deletions,6 incontinentia pigmenti,7 and Rhett syndrome.8

These disorders are fairly rare. And while women who carry the DNA for these disorders are born, they often show other symptoms.

People who think they could be at risk for having (or carrying) an X-linked condition should consider speaking to a doctor or genetic counselor. To learn more about genetic counseling or to find a genetic counselor in your area, visit http://nsgc.org.

Are there other reasons why a family might have more girls than boys?

There are lots of things that people think could affect the sex ratio including diet, illnesses, cigarette smoking, pollution in the environment—even how warm it is in a particular year.9 It’s worth noting, though, that the impact of any of these things is pretty small. You can see a difference in an entire population, but it wouldn’t be noticeable in a single family.

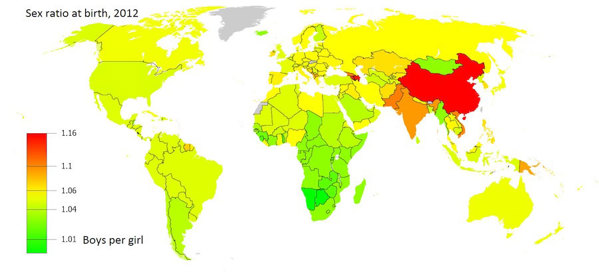

It also turns out that the human sex ratio isn’t exactly 50:50 to begin with. On average, around 105 boys are born for every 100 girls. This pattern has been seen over and over again, across many different countries and time periods.10–12

We don’t know why the sex ratio is slightly biased towards boys. However, we do know that sperm has a 50:50 ratio of X and Y chromosomes (which determine the child’s sex), even for men who have mostly sons or mostly daughters.13,14 So, some scientists think that the bias has something to do with more male embryos surviving to birth.15

However, there’s an interesting exception to this rule. In times of stress, female babies are more common!

There are quite a few studies that found an increase in the number of female babies after stressful incidents. This includes natural disasters (often large earthquakes),16 long periods of famine,17 and even events like the September 11 attacks.18–20

Why are more girls born during tough times? Scientists don’t know for sure, but they have a few guesses. One possibility is that females can more reliably have children of their own, while males might be more likely to be left childless.21 Another possibility is that males take more energy to raise, so it’s more economical to have females.22

Now, this doesn’t mean that a family with a lot of girls is “stressed out,” or that you can ensure you have a boy by de-stressing your life.

Really, the only thing that we know for sure is that no one factor really affects the gender balance that much. The sex ratio is surprisingly hard to change, given the number of things that could potentially tip the scales. So, while a gender bias could run in your family, there’s still a very real possibility that it’s all just up to chance.

Author: Ellen Bouchard

When this answer was published in 2019, Ellen was a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Developmental Biology, studying the genetic and molecular basis of how the vertebrate nervous system develops in Will Talbot’s laboratory.

Skip Navigation

Skip Navigation