I have Sectoral Heterochromia. What eye color will my child have?

May 8, 2012

- Related Topics:

- Heterochromia,

- Eye color,

- Pigmentation traits,

- Rare events,

- Mosaicism,

- Chimera

An undergraduate from Georgia asks:

“Hello, I am curious about what eye color my child might have. I have what I think you call Sectoral Heterochromia. One eye is green, the other is split 50/50 directly in half. Green on top/brown on bottom. My wife has blue eyes. Will my child have different colored eyes too? If not, what color will they be?”

That’s a great question! Most of the time, this difference in eye color can’t be passed down in people. Although we don’t always know what causes sectoral heterochromia, it can come from something that happened during development, an eye injury, or any of a number of non-genetic causes.

When any of these is the culprit, it can be very tricky to predict your child’s eye color. We’d have to know whether your real eye color is green or brown.

Do you have the version of genes for green eyes but something happened to turn part of one eye brown? Or are you genetically brown eyed but something happened to change them to mostly green?

If it’s the first case, then your kids would most likely have blue or green eyes (depending on whether you carry blue eye genes or not). In the second case, almost any eye color is possible depending on your genes. Click here to learn more about eye color genetics.

Inherited syndromes and new mutations

Although it’s rare, sectoral heterochromia can sometimes be inherited. When parents pass down different colored eyes to their children, it’s often due to something called Waardenburg syndrome.

If you have Waardenburg syndrome, then each of your kids has a 50% chance of getting the gene that causes it, but they won’t necessarily be affected just like you. Because of how this condition works, there’s a huge variety of symptoms (click here to learn more).

Sometimes there are no symptoms at all. People with this syndrome might never know unless one of their kids ends up with different colored eyes.

Other times, people with Waardenburg syndrome end up with both eyes a really pale blue. You wouldn’t necessarily know that these people have a genetic condition, either.

And sometimes they have sectoral heterochromia. All of this makes it very hard to figure out the chances that a kid will end up with sectoral heterochromia based on his or her parents.

What we can say is that if your sectoral heterochromia is caused by Waardenburg syndrome, each of your kids has a 50% chance of getting the gene version. We can’t say how likely that gene is to go on and make anything out of the ordinary happen with the child’s eye color.

There are other genetic ways to end up with heterochromia. Most of these aren’t passed down to your kids and are the result of some sort of change to your DNA during development.

Random Chance and Developmental Biology

Another way this might happen is if a person is “mosaic”. When we say mosaic, we’re not referring to the tiled wall murals made in ancient Rome. Instead we’re talking about someone who has cells with two different types of DNA.

In art, a mosaic is made by putting little pieces of different colored glass or other material together to make a picture or decoration. In people, it happens by putting together cells with different DNAs to make a person.

All of our cells have the same DNA, but a mosaic person or animal has some cells whose DNA is different from the rest. Just like a complete mosaic is made of different-colored tiles, the mosaic person’s cells still come together to make their whole body.

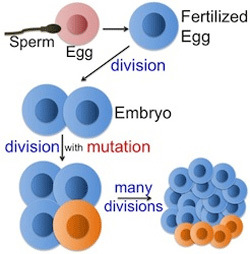

Usually what happens is that early in development, one cell picks up a mutation in its DNA. Maybe some chemical damaged it or the cell simply made a mistake when it copied its DNA.

Whatever the cause, now all the cells that come from that cell have the different DNA. If, for example, the mistake happened when the fertilized egg first divides, then half of the person’s DNA will have different DNA.

And don’t think that this is weird… everyone is a mosaic to one extent or another. The difference here is that the DNA difference happens to be in an eye color gene so we can see its effects. The person has different colored eyes.

Other mosaics have changes in DNA that doesn’t show up. There folks are hidden mosaics.

What this means is that a mosaic can’t pass down sectoral heterochromia. Her eggs or his sperm will have one set of genes or the other, but one cell can’t be mosaic on its own.

So if your eye color were the result of mosaicism, then you’d pass either a brown or a green eye color gene to your child. You would not pass a combination of the two genes. Your child would not get sectoral heterochromia from you.

Chimeras: A Two-Person Fusion

And finally, we get to a very rare way this can happen: chimerism. Chimeras also have cells with different DNA. The big difference between mosaics and chimeras is where those cells come from, and how different the DNA is.

Although it’s very rare, chimeras can happen when fraternal twins fuse together at a very early stage. They basically have some cells with the DNA of one twin and some cells with DNA from the other twin.

This also means that the cells will be as different as any two siblings. And as you are undoubtedly aware, siblings can be very different!

Most of the time, though, a chimera doesn’t have any visible signs. You would never know that they had two different sets of DNA. The only way to tell is if they have different DNA for body parts that we can see, like skin or eyes.

If you were a chimera, then we would say that one twin was going to have brown eyes and the other green. Your eyes are made up of cells from both.

But again, just like mosaics, you would not pass your sectoral heterochromia to your child. Your child would get either a brown or a green eye color gene, not a combination of the two.

Chances are, though, you’re not a chimera. There are so many ways that a person can end up with different colored eyes that figuring out the cause can be pretty tough! What we can say, though, is that when people have heterochromia, most of the time it never shows up in their kids.

Author: Amy Johnson

When this answer was published in 2012, Amy was a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Biology, studying mammalian cell cycle control in Jan Skotheim’s laboratory. Amy wrote this answer while participating in the Stanford at The Tech program.

Skip Navigation

Skip Navigation