What are the chances of having children with Down’s syndrome?

July 25, 2012

- Related Topics:

- Trisomy/Aneuploidy,

- Translocation

A curious adult from Angola asks:

This is an interesting question. Usually if there are cases of Down syndrome in a family, the other family members don’t need to be worried about their kids. This is because 95% of the time Down syndrome happens randomly because something goes wrong when an egg or sperm is made.

There is nothing about the parents’ genes or bodies that cause it. It is just the natural error rate for making sperm or eggs. And, correcting for the parent’s age, everyone’s risk is about the same. So there is no way someone could be carrying a “silent” form of this type of Down syndrome without them having the disease themselves.

Occasionally parents can pass on genes that make it more likely that their kids’ kids (the parent’s grandchildren) will have Down syndrome. Scientists aren’t totally sure, but it isn’t thought to be very common.

In the other 5% of cases, children inherit Down syndrome from a healthy parent. Luckily there are very accurate tests available that can figure out if this someone carries this silent risk for Down syndrome in their DNA.

So if your future spouse’s family happens to have this form of Down syndrome in the family AND this spouse inherited the DNA for it, then there is a chance your future kids could be at a higher risk than other kids. To be specific, if your spouse is a man, then there is about a 3% chance that your children would be affected. And if she is a future wife, then the risk is 12%. (Click here to learn more about where exactly these numbers come from.)

This is, on average, about 24 or 96 times higher risk than usual (depending on age of course). But like I said, most of the time it won’t matter if someone in your spouse-to-be’s family had Down syndrome.

To understand how things work in the 5% of cases where Down syndrome can run in families, we need to take a step back and learn what Down syndrome is. And to do that, we need to go back even further and talk about chromosomes.

Chromosomes

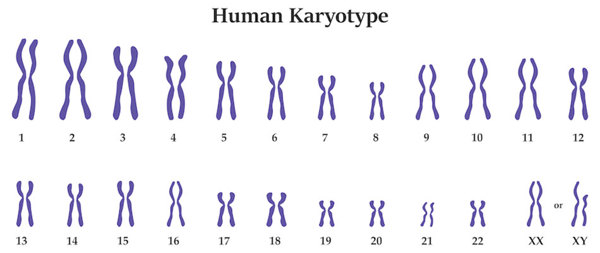

Chromosomes are long strands of DNA that have the instructions for making a living thing. Humans have 23 different chromosomes.

They get a set of 23 from mom and a set of 23 from dad for a total of 46. The chromosomes are called 1-22, and then there are the X and Y chromosomes (females have two X’s and males have an X and a Y).

Occasionally someone will get an extra copy (three total copies) of a chromosome. Most of the time having an extra chromosome is fatal and results in a miscarriage, but sometimes the person can survive (although they often have problems).

Chromosome 21 is one of these better tolerated chromosomes. Many times having a third copy of chromosome 21 leads to miscarriage, but if the baby survives it will have Down syndrome.

So how does a person end up with three copies of one chromosome? This can actually happen in two different ways.

In one you end up with three separate copies of the extra chromosome. This is the 95% of Down syndrome cases that don’t usually run in families.

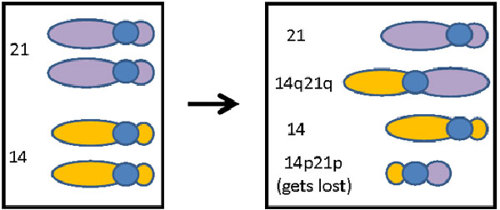

In the other 5% of cases, the extra chromosome gets stuck to another chromosome. So, for example, chromosome 14 and chromosome 21 can end up stuck together.

For reasons we discuss below, these people are often fine even though they technically have only 45 chromosomes because two are stuck together. They’re fine that is until they start trying to have children. Then that stuck together chromosome can cause all sorts of problems.

I won’t go into too much detail on how the uninherited form of Down syndrome works (click here to learn more if you’re interested.) Instead I will focus on how two chromosomes can get stuck together and how that can make Down syndrome run in families.

How Chromosomes Get Stuck Together

To understand how chromosomes can get stuck together, we need to focus a bit more on a chromosome. A chromosome consists of two arms connected by something called a centromere.

For human chromosomes 13, 14, 15, 21 and 22, one arm is very short and contains very little useful information. These are called acrocentric chromosomes.

Sometimes two of these chromosomes break and the two long arms get stuck together. The two short arms are lost but that’s OK. The person is perfectly fine.

This is because they still have all of the important genetic information: it is just packaged differently. And this kind of balanced translocation (as scientists call it) is more common than you might think. Around 1 in 1000 people have two of their chromosomes stuck together. They might not even know it until they start trying to have kids.

Inheriting Down Syndrome

Normally, when cells divide, you want each cell to end up with all 46 chromosomes. This isn’t true for making a sperm and egg though. For these cells, you only want half that number.

So each sperm or egg gets one copy of chromosome 1, one copy of chromosome 2, etc. This is so that when the sperm fertilizes the egg, you end up with 46 chromosomes.

What this all means is that when a sperm or egg is made, the copies of each chromosome need to be separated from each other. In other words, the two copies of chromosome 1 need to be separated, the two copies of chromosome 2 and so on.

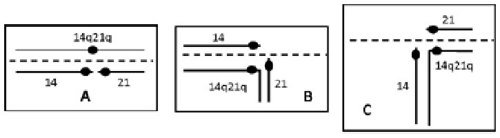

To separate, the chromosomes line up with their matching partner across the cell. But when two chromosomes get stuck together, they can’t both line up with the right partner.

The cell does the best it can with three possible results shown in the image below. One sperm or egg cell will get the chromosomes above the dotted line, and one will get the chromosomes below the dotted line:

A) One inherits a combined chromosome 14+21, while the other gets the regular one 14 and 21

B) One will not inherit any of chromosome 21, while the other gets an extra copy

C) One will not inherit any of chromosome 14, while the other gets an extra copy

When the sperm or egg from these last two cases combines with the egg or sperm from the other parent (assuming the other parent’s chromosomes are normal), then you can end up with too few or too many chromosomes.

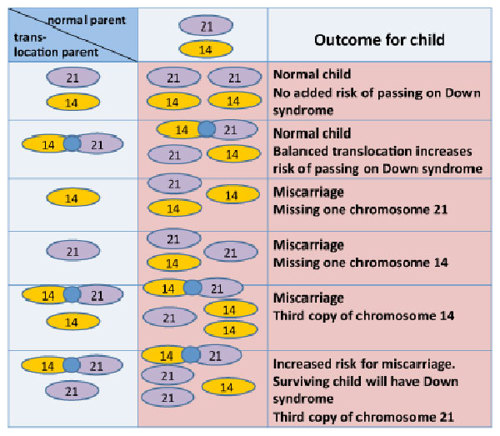

I’ve outlined the six possible outcomes in the table below:

As you can see, more than half the time the pregnancy will end in miscarriage. Most of the surviving pregnancies will be normal (although a little under half of these will have pregnancy issues too) and a small percentage will have Down syndrome. This is where the 3% chance for men and the 12% chance for women we talked about before came from.

Your Spouse-to-be

So what about your situation? Well, this is where you need to know a little bit about your spouse-to-be’s family.

If there is just one person in his or her family with Down syndrome, it was probably just bad luck (although it could be the other type as well). Remember that 95% of cases are random.

But if women in his or her family tend to have a lot of miscarriages and there is someone in every generation (even for just the last generation or two) with Down syndrome, then there might be one of these “Robertsonian translocations” in the family.

Probably the best thing to do is to visit a doctor or a genetic counselor. Even if a translocation runs in your spouse-to-be’s family, it doesn’t mean he or she has it.

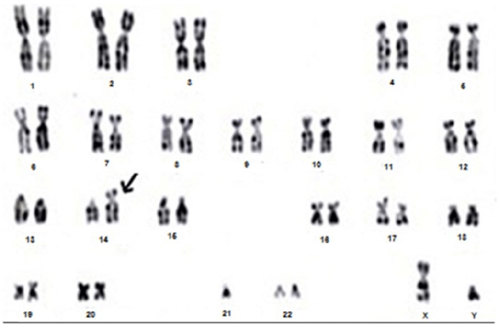

Karyotypes (which doctors use to see your chromosomes, like the picture above) are pretty easy to perform, so your spouse-to-be could have his or her karyotype done. Then you would know for sure if he or she has a translocation.

Skip Navigation

Skip Navigation