If men and women both have the same genes, how is it that men get traits that women do not?

September 10, 2015

- Related Topics:

- Developmental biology,

- Y chromosome,

- Gene expression,

- Genetic sex

A science-minded software engineer from Idaho asks:

“Do both sides of a base pair represent genes? If so, does that mean that some genes are a mirror image of other genes? Or do some segments of DNA only have genes on "one-side" of the helix, while the other side is just filler?”

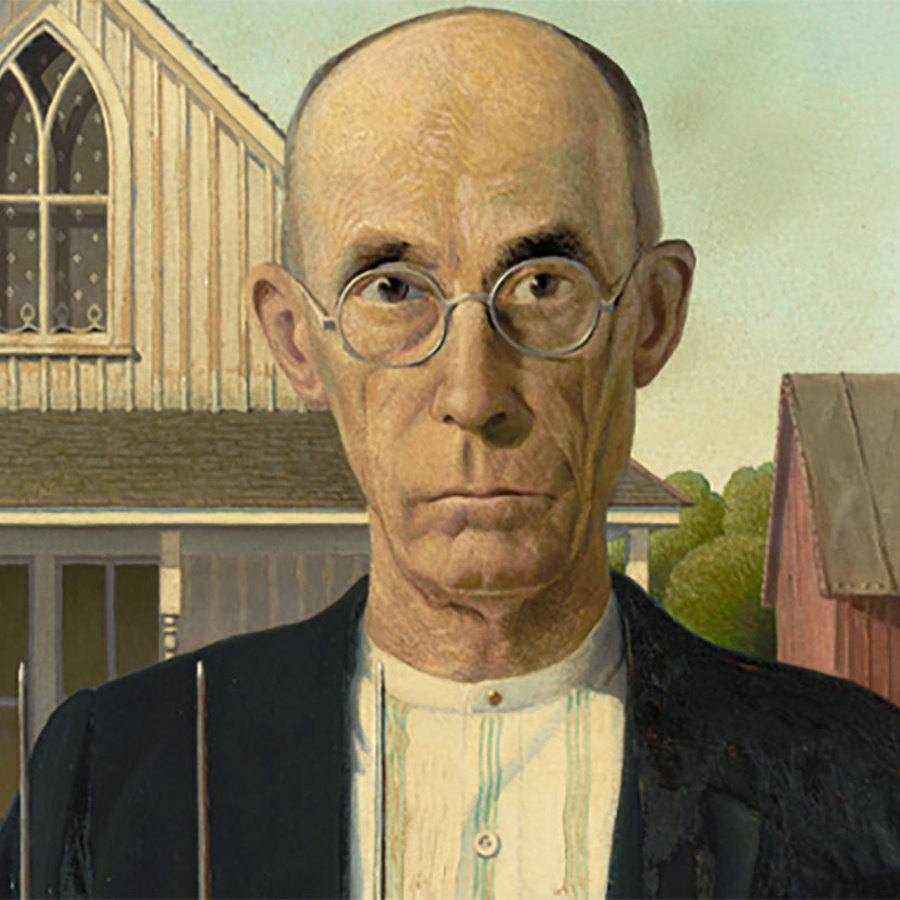

It isn’t quite right to say that men and women have exactly the same genes. Men in fact have several dozen genes that women don’t.

It is these few genes that cause someone to become biologically male. But they don’t work by themselves.

That small number of genetic differences helps set off a cascading chain of events. They cause different steroid hormones to be made. Then those hormones turn on other genes. That means a relatively small genetic difference can make a big impact.

These genes can do so much by essentially changing how many of the rest of the genes get used. This changed “gene expression pattern” is one of the big reasons men and women have different traits.

It’s also why hormone therapies are so effective: giving artificial hormones affects a ton of different genes, which can have widespread effects.

Controlling Gene Expression

Humans have the same 20,000 to 25,000 genes in each of their cells. These genes act like an instruction manual and play a big part in making us who we are.

Each gene has the instructions for making a small part of us. One tells your body how to make a pigment that causes your hair to be a certain color, another instructs your body on how to break down the sugars in milk, and so on.

As I said, all the cells in our body have the exact same set of genes, and these cell types can differ greatly in appearance and function. This is because each different cell type only reads a subset of its genes. A heart cell only reads the genes it needs to be a working heart cell and ignores the genes the brain cell needs.

Think about a cell like a construction team tasked with building a house. In the central office is a manager with the blueprints to make every structure in the city. The manager copies out instructions, sends them to her workers outside, and the workers build the house.

This is similar to how our cells work. Our genes are kept in a central structure called the nucleus. Individual genes are copied to make messenger RNA (mRNA), and the information in the mRNA is used to build proteins, which do the important work in the cell.

With the construction team, it’s easy to understand why they only build the house and not the whole city. The manager can copy the parts of the manual needed to make the house while ignoring the parts related to skyscrapers or hospitals or anything else.

Our cells control the expression of our genes in similar ways. A developing brain cell has transcription factors that make sure the genes needed to make a brain cell get copied to mRNA. They can also make sure that the cell doesn't express the genes for heart cells or lung cells or anything else.

Explaining how a heart or brain cell pulls this off is a tricky business. After all, they all have the same genes for the same transcription factors! Click here to see how they do it.

But making someone biologically male or female is much simpler. Some of the extra genes biological men have are, you guessed it, transcription factors.

SRY: the Master Switch

Our 20,000-25,000 genes are grouped together on 23 pairs of chromosomes. 22 of these pairs are the same for men and women. We call these autosomes.

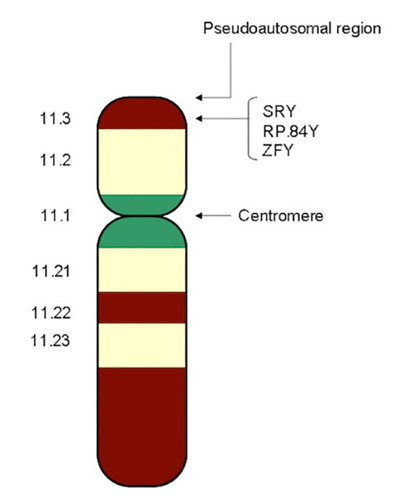

However, it’s the 23rd pair, the sex chromosomes, where we see the difference between men and women. Generally, women have two X chromosomes while men have an X and a Y. It is the Y chromosome that has the instructions that cause men and women to have different traits.

The Y chromosome only has ~72 genes on it but it doesn’t even need that many; it mostly comes down to a single one. This single gene, SRY, is able to get the ball rolling on giving a body male traits.

Its name stands for Sex-determining Region Y, because it’s the part of the Y chromosome that causes XY individuals to become biologically male. SRY contains the instructions for a transcription factor that ultimately controls the expression of many other genes that make men different from women.

Early in development, male and female embryos develop identically. But when SRY is there, the embryo starts to develop male traits. Without SRY, the default is for the embryo to develop as female.

One of the key things SRY does is to cause the development of testes which make lots of a particular hormone: testosterone. This testosterone then works with a transcription factor called the androgen receptor (AR), whose gene is on the X chromosome.

As you can guess, both men and women make AR. But people with a Y chromosome make lots more testosterone, which pushes AR into overdrive. This causes differences in the expression of genes responsible for giving men beards, causing male pattern baldness and lots more.

Now to be clear, a woman is not simply a man without an SRY-induced gene expression pattern. Instead of testes and testosterone, people without a Y chromosome have ovaries and different hormones (estrogen and progesterone). And like testosterone, estrogen and progesterone have their own transcription factors, the estrogen receptor (ER) and the progesterone receptor (PR).

The extra estrogen and progesterone that women make (or take as a hormone therapy) causes ER and PR to turn on and off a set of female specific genes. And this leads to even more female specific traits.

Dr. Mike Brown

When this answer was published in 2015, Mike was a post-doctoral fellow in the Department of Biology, studying host-pathogen interactions in Mary Beth Mudgett's laboratory. Mike wrote this answer while participating in the Stanford at The Tech program.

Skip Navigation

Skip Navigation