How accurate are Rh blood type tests?

August 6, 2019

- Related Topics:

- Blood type,

- Rh factor,

- Genes to proteins,

- Genetic variation,

- Editor's choice

A curious adult from California asks:

“How accurate are blood typing tests? My husband and I have Rh- blood type, but we have an Rh+ child. (And I am 100% certain my husband is the father!)”

As you’ve noticed, those Rh blood tests aren’t always 100% accurate.

The Rh blood tests try to answer the question: “Does this person have any Rh protein on their blood cells?”

If the test detects any Rh protein, the person is labeled Rh+. If no Rh is detected, the person is labeled Rh-.

But if someone only has a little bit of Rh protein, the test might not be able to detect it. In this case, the test might incorrectly label someone as Rh-.

This can lead to some confusing examples where a child has an “impossible” blood type – even when you’re 100% certain of the parents!

Inherited Rhesus (Rh) factors: what even are they?

Rhesus factor is a category of antigens that can be found on the surface of red blood cells. There are many different types of Rh factors and they all come from two genes: RhD and RhCE.

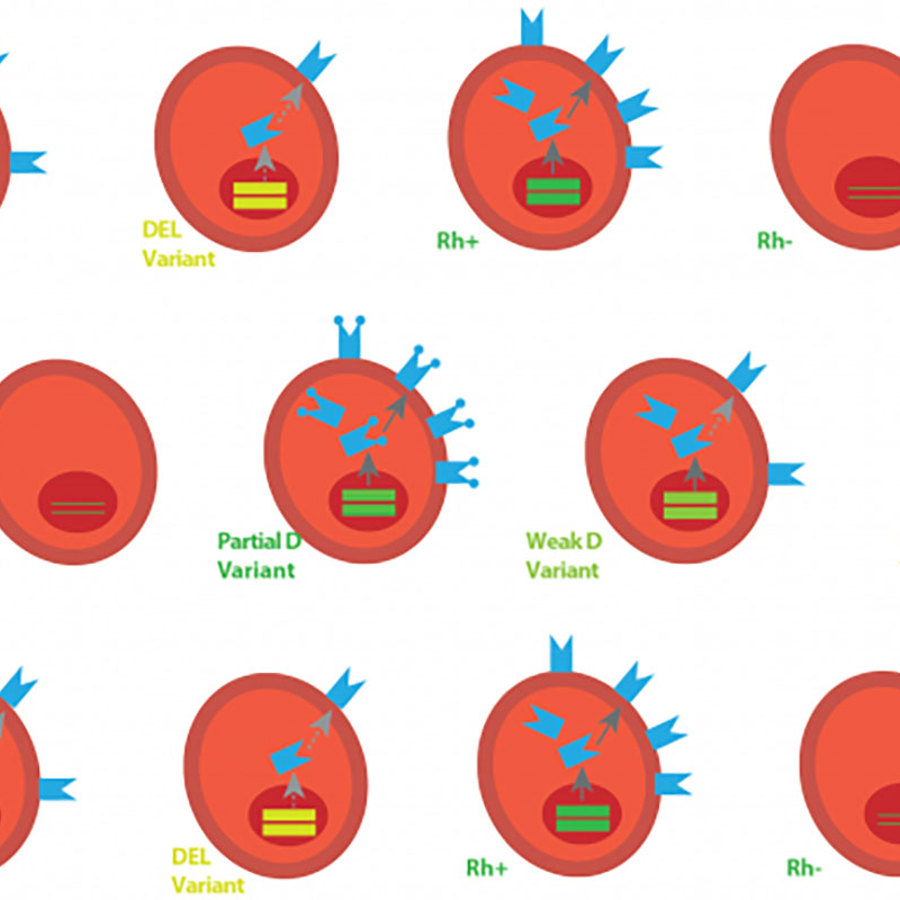

The Rh blood factor test only looks at a single antigen that comes from the RhD gene: the D antigen. When a blood test says someone is Rh+, that means the individual has the D antigen present. If the test says someone is Rh-, then the test did not detect any D antigen.

The standard blood-type tests only look at the D antigen, because it has the largest effect on whether you’ll have an immune response during pregnancy and blood transfusions. Because of this, it will be the only one I discuss here.

RhD comes in different varieties

Everyone has two copies of their RhD gene: one from mom and the other from dad. If even one copy expresses the D antigen, then that person will test positive for having the D antigen.

The most common versions of the RhD gene are:

- RhD: this gene variant produces a normal amount of common D antigen

- Absence of RhD: some people are entirely missing the RhD gene. Without this gene, they don’t produce any D antigen

A person will test Rh- usually because they have no copies of the RhD gene. Two parents that don’t have any copies of the RhD gene can’t have a child that has an RhD gene.

However, there are different varieties of the RhD gene. And the blood factor test isn’t always good at detecting these other varieties.

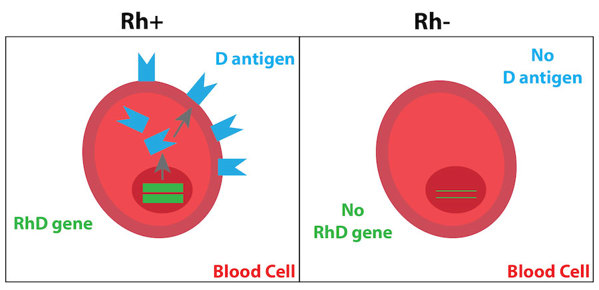

Some of these different RhD genes lead to different amounts of D antigen, while others can lead to different shapes of D antigen. There are three variations in the RhD gene that I will discuss:

- Partial D: this gene variant leads to a D antigen with a slightly different shape

- Weak D: this gene variant makes the same amount of D antigen as the normal RhD gene, but it has a slight change that stops it from getting to the surface of the cell

- DEL: this gene variant makes a reduced amount of D antigen

The blood factor test: what does it REALLY tell you?

In your case, the tests say that neither you nor your partner have a D antigen (Rh-). And yet, the test says your child does have a D antigen! So why is that?

This has a lot to do with the accuracy of the tests, and whether or not they can detect strange D antigens that are produced by variants of the RhD gene.

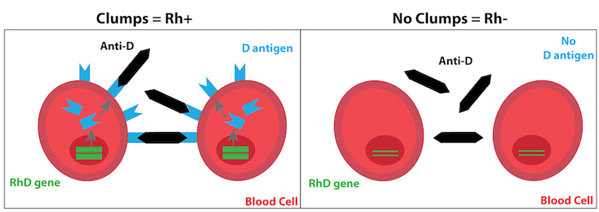

A standard Rh factor blood test looks to see whether the D antigen is present. The D antigen has a certain charge and shape. The test ingredient (called anti-D), has a charge and shape that likes to bind to the D antigen—and the D antigen only! It’s a lot like the way two puzzle pieces will precisely fit together.

If the D antigen is present, anti-D will stick to it. And it can stick to several D antigens at a time, even if they’re on different cells! This means anti-D can cause the cells to clump together. However, if D antigen is not present, the cells will not get stuck together. If the cells stick together when anti-D is added, then the person is considered to be Rh+.

Problems can occur during the test for a lot of different reasons. The test only looks at clumping. If there isn’t much D antigen for the anti-D to stick to, the cells might not get glued together.

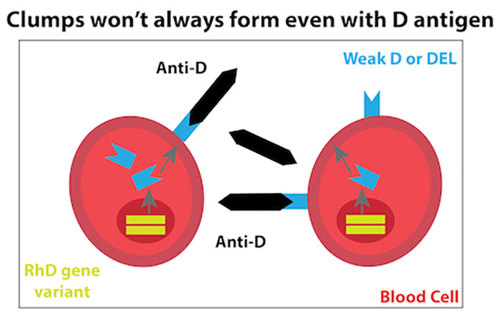

Someone that doesn’t have a lot of D antigen on the surface (as is the case for weak D and DEL) may test negative, even though they technically have the D antigen. Their cells may not clump much when anti-D is added. So the clinic may say that person in Rh-, even though they technically have the D antigen.

Problems can also occur during the test when someone’s D antigen looks a bit different than the normal D antigen. Remember how anti-D fits with D antigen like perfect puzzle pieces? If someone has a slightly different version of the D antigen, anti-D might not recognize it.

This can be the case with partial D. Because the anti-D doesn’t recognize the D antigen, the cells don’t get stuck together. The clinic may say the person is Rh-, even though the individual does have a D antigen.

So why is it that two parents have no D antigen, and yet the child’s test says they do have a D antigen? Basically, it’s possible that one parent actually does have D antigen. However, it could be shaped differently, or the parents don’t have a lot of D antigen, so it was not detected in the blood factor test.

In summary, blood tests are pretty good at recognizing normal D antigens, but sometimes people have a variant of the D antigen that is less common. These variants can be hard to detect in a blood factor test, and a test might label a person as Rh- even though they have D antigen!

Author: Rebecca Culver

When this answer was published in 2019, Rebecca was a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Genetics, studying bacteria in the gut microbiome in KC Huang's laboratory. She wrote this answer while participating in the Stanford at The Tech program.

Skip Navigation

Skip Navigation