Why don’t silent mutations cause problems? What makes them silent?

October 1, 2015

- Related Topics:

- Mutation,

- Molecular biology,

- Genes to proteins

A curious adult from California asks:

Silent mutations are DNA changes that don’t change a gene’s “meaning.” They are like trading the words shady and unscrupulous in a sentence. Both words are usually pretty interchangeable.

But not always of course. No one would say a tree is unscrupulous (unless it is an evil Ent of course).

And sometimes even using ‘unscrupulous’ correctly can affect a sentence. If you don’t know what the word means, you may pause to look it up. This pause might affect the flow of the sentence and so compromise whatever emotion the author was trying to evoke.

It turns out that most silent mutations are harmless because “synonyms” in the cell don’t have other meanings. In the example here, shady always means “of doubtful honesty or legality” and never “giving shade from sunlight.”

But one way silent mutations can sometimes affect how a gene works is by making the cell pause while it is reading a gene. Just like we might have to pause to look up a tricky word.

These changes can have surprisingly big effects too. For example, they can sometimes make a virus not respond to medicines any more. This can obviously be very bad.

To understand how replacing one word with a different one with the same meaning might affect a gene, we need to step back and talk about what a gene really is. And what a protein is.

Genes Have the Instructions for Proteins

Each of your genes has the instructions for one small part of you. So there is a gene that helps determine your eye color, another that does blood type and so on.

Well that isn’t exactly right because the gene doesn’t actually do any of this. Instead genes are the assembly manual for proteins, and proteins do the actual work.

So there is a gene that has the instructions for making a protein that colors your eyes. And another one that has the instructions for a different protein that gives you your blood type. And so on.

These instructions are written in a very simple code. Much simpler than English for example.

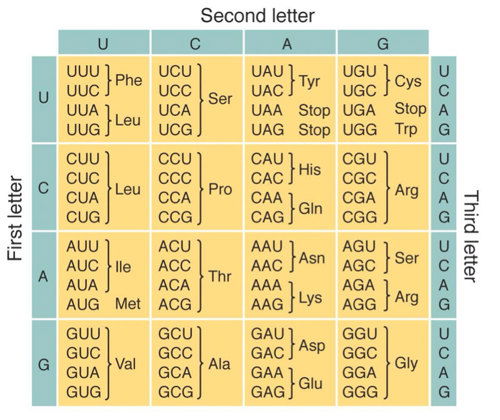

The alphabet is made up of just four letters: A, T, C, and G. And the vocabulary is just 64 three-letter words. That is all it takes to make the genes of every living thing on Earth.

Silent mutations can happen because some of these three letter words “mean” the same thing. The words ‘shady’ and ‘unscrupulous’ are usually synonymous so it usually won’t matter if you switch them. Similarly, a silent mutation doesn’t change the basic protein instructions.

The Meaning of Words (Codons)

As I said, a gene has the instructions for making a protein and a protein does a certain job in the cell. But what is a protein?

It is really just a bunch of molecules called amino acids strung together in a certain order. There are around 20 of these amino acids.

Each of the 64 words in the genetic code stands for one of these amino acids. So when the word (or codon) ‘ATG’ is in the gene, the cell adds the amino acid methionine (Met) to the protein. And if the word is ‘AAG’, then the cell puts in the amino acid lysine (Lys).

But AAG isn’t the only word that means Lys. AAA also means Lys.

So if there is a mutation that changes an AAG to an AAA, the cell will still put in a Lys. This is a silent mutation.

Sounds simple enough — basically adding amino acids one after the other until a protein is made. Which explains why silent mutations are usually pretty harmless. They don’t change the amino acid that gets put in.

But there is more to a protein than its string of amino acids. To do its job properly, that string needs to fold up like origami into the exact right shape. And sometimes having a silent mutation can affect this step.

Folded While You Wait

The key to understanding how silent mutations might affect a protein is realizing that the proteins are folded as they are made. So it starts to fold even before it is finished.

Parts of the protein get folded before the next part comes out. Each of these folded parts is called a domain. These domains then all fold on each other until you get a working protein.

This whole process depends on the amino acids being connected together at a certain rate. If it slows down, pauses, or even speeds up, the protein can end up in the wrong shape. It can misfold.

This is where silent mutations can gum up the works. It turns out that some words are easier for a cell to translate than others. The word ‘shady’ is a whole lot simpler than ‘unscrupulous.’

What this means is that when the cell gets to a word it struggles with, the whole process pauses until it figures it out. If the pause is long enough, the parts of the protein that are hanging out there will start to fold up on their own.

If only part of a domain is out there, it will still fold into something. And that might mess up the whole folding process, like a failed origami duck.

You can imagine the opposite happening as well. A complete domain is put together and then there is one of those hard-to-read codons that stops everything. This might then give that part of the protein time to fold properly before moving on to the next section.

Rarely Used

In all of this I keep saying that a protein has trouble with certain codons. This trouble comes from how common the translating machinery is for each codon.

There are certain molecules called transfer RNAs (tRNAs) that bring the right amino acid to the place where proteins are assembled, the ribosome. The more common a tRNA is, the more quickly its amino acid can be added to the growing protein chain.

So codons that have a lot of their tRNAs floating around in the cell get translated quickly and the rarer tRNAs take longer. It is as simple as that!

Author: Dr. D. Barry Starr

Barry served as The Tech Geneticist from 2002-2018. He founded Ask-a-Geneticist, answered thousands of questions submitted by people from all around the world, and oversaw and edited all articles published during his tenure. AAG is part of the Stanford at The Tech program, which brings Stanford scientists to The Tech to answer questions for this site, as well as to run science activities with visitors at The Tech Interactive in downtown San Jose.

Skip Navigation

Skip Navigation