If a female (XX) has a baby with a 'supermale' (XYY), is the baby more likely to be male?

May 29, 2014

- Related Topics:

- Reproduction,

- Genetic sex,

- Chromosomes,

- Trisomy/Aneuploidy

An undergraduate from California asks:

"If a female (XX) has a baby with a “supermale” (XYY), is the baby more likely to be male? I couldn’t find any studies on this..."

The quick answer is that “supermale” (XYY) dads have an equal chance for having boys or girls. Which might seem weird at first.

After all, dads decide the sex of the baby. If he passes a Y, he’ll have a boy and if he passes an X he’ll have a girl. And a supermale has one X and two Y’s right?

He does, but it doesn’t mean he will make more Y sperm. Turns out he pretty much makes the same number of X and Y sperm, which means an equal chance for a boy or a girl.

Making a Boy or a Girl

Almost all humans have 46 long strands of DNA called chromosomes. This is where all of the instructions for making a person are found. These instructions are needed for each person to function every day.

I know it seems like a very long time ago, but you were once a baby. You came to be when an egg from your mom fused together with the sperm from your dad.

An egg has 23 chromosomes and so does a sperm cell. When sperm and egg fuse together, the newly formed baby will have 46 complete strands of DNA. Half of the DNA will have come from mom and half of the DNA will have come from dad.

Each of our chromosomes usually come in pairs. So we have two copies of chromosome 1, two copies of chromosome 2 and so on up to chromosome 22.

One chromosome from each pair ends up in a sperm or an egg. This is how we end up with 23 pairs again when an egg and a sperm fuse together.

The 23rd pair, the sex chromosomes, is special. They are the major factor in determining whether you are a boy or a girl.

Women usually have two X chromosomes (they are XX). This means that each of their eggs has an X chromosome.

Men are different though. They are XY meaning they will make sperm that have either the X or Y sex chromosome.

When an egg and a sperm fuse, you usually end up with either an XY or an XX baby. This is why dad determines whether a couple will have a boy or a girl.

Of course this doesn’t explain where an extra Y comes from. It actually can happen when there is a mistake during sperm production.

The Extra Y Happens When Sperm is Made

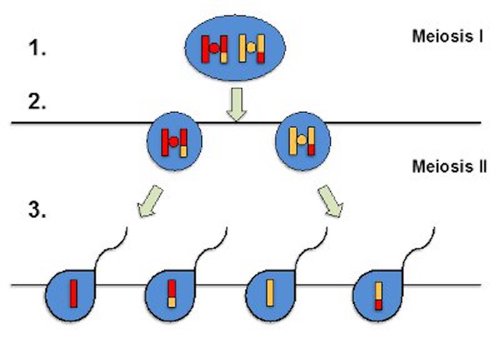

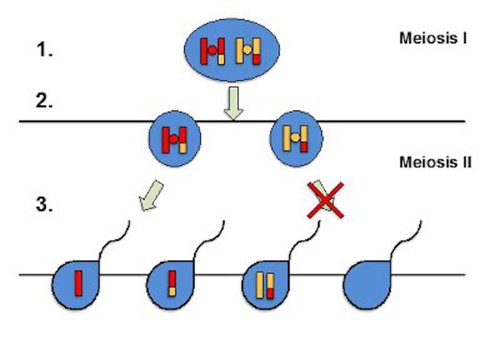

Sperm and eggs are made through a process called meiosis. During meiosis, the chromosome numbers go from 92 to 46 and finally to the 23 of sperm and eggs. Here is a diagram of what that looks like focusing on a single chromosome pair:

In the first step, the cell copies each of its chromosomes meaning there are now 23 sets of four copies. In the second step, the cell containing four copies of each chromosome divides making two cells which have two chromosomes each (1 cell -> 2 cells). In the third and final step, the cells divide again so that each cell only has one copy of each chromosome (2 cells -> 4 cells).

This is a pretty complicated process and things sometimes go wrong. Our cells are good at catching these mistakes but occasionally mishaps will get through. And then you can end up with an extra or a missing chromosome.

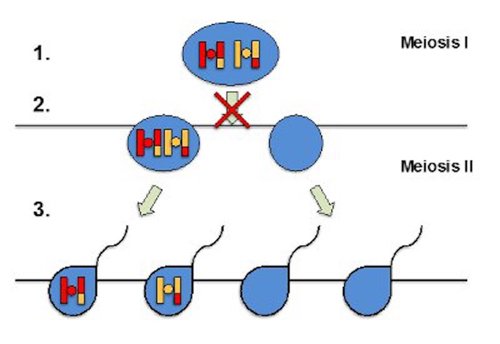

As you can see below, there can be a problem in the second step when four chromosomes can go into one cell and none in the second cell:

Or as you can see below, there can be problems in the third step when two chromosome copies go into one cell and no chromosome copies go into the other cell:

These are the ways an extra Y chromosome can sneak into a sperm cell and fuse with an X egg to make a XYY male.

These types of mistakes are usually random and often have devastating effects. But not always. For example, men with an extra Y are usually perfectly fine.

Around 1 in 1,000 boys and men are XYY but many don’t even realize it until they take a genetic test. This is because XYY males don’t look or act any different than XY males - they develop normally and are able to have children. The extra Y chromosome doesn’t make too much of a difference.

Many years ago, doctors thought XYY males tended to be more aggressive and likely to commit crimes than XY men. Research has shown this is wrong: no connection has been found between criminal behavior and the extra Y chromosome. So far, research shows that XYY men tend to be slightly taller than average. Links have also been made between being XYY and having some learning difficulties, but this is fairly uncommon.

XYY Dads Have a 50/50 Chance of Having a Boy or Girl

As I said earlier, males have an X and a Y chromosome, which means they have sperm that have either an X or a Y chromosome. It is much more complicated for XYY males.

As a first guess you might think that they’d make two Y containing sperm for each of their X containing sperm. This would mean that they would be twice as likely to have boys.

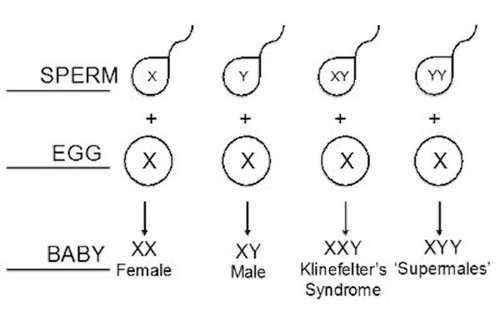

Now that we understand how sperm is made using meiosis, you can see that this would not be the case. Instead you might predict that they would have either X, Y, XY, and YY sperm. Upon fusing to an egg that has an X chromosome, you would predict that the children would be any of the following:

But this isn’t actually what happens. XYY men don’t have more of a chance to have XXY or XYY children, or more boys in general. It is unclear why this is.

One idea is that our bodies have quality control processes that make it less likely that any embryo with too many or too few chromosomes will come to term. Our bodies have many protective mechanisms and checkpoints to ensure that we have the right amount of DNA.

So we know that XYY males do not have more baby boys and are not more likely to have kids with extra X’s or Y’s. Scientists are still trying to figure out how these checkpoints work to better understand our bodies and prevent diseases that come from having too many chromosomes!

Author: Natalie Chavez

When this answer was published in 2014, Natalie was a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Biology, studying mechanical signaling in epithelial cells in James Nelson's laboratory. Natalie wrote this answer while participating in the Stanford at The Tech program.

Skip Navigation

Skip Navigation