What causes cleft chin?

June 8, 2023

- Related Topics:

- Complex traits,

- Appearance,

- Genetic myths

A grandmother from the US asks:

"What causes cleft chin?"

A lot of people have cleft chins. Some people think they look good, others maybe not so much. There’s no deeper meaning behind having one, but our genetics do tell our bodies whether or not one will be made.

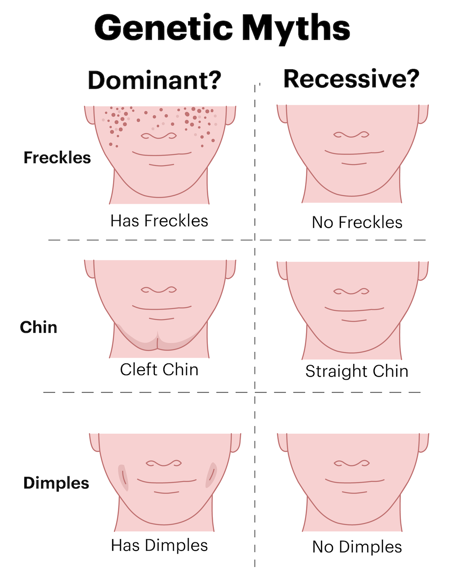

You may have heard, or even have been taught in school, that cleft chin is one of those heritable traits that follow predictable inheritance patterns. Something like, you have a cleft chin, at least one of your parents must have it too. But if your parents don’t and you do?

It’s not a reason to panic! We know now that it’s a bit more complicated than that, and not so easily predicted. There are many different genes that act together to influence this physical trait.

What is cleft chin?

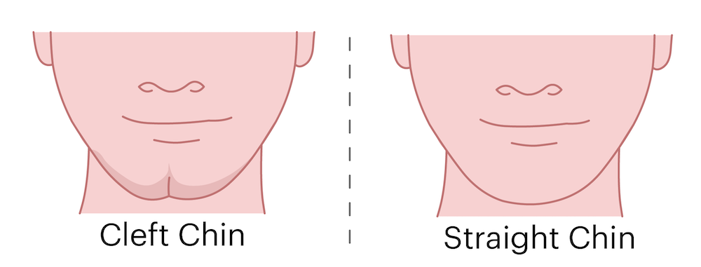

If you have a cleft chin then you should be able to see a dimple that runs from the bottom of your jaw to about halfway up to your mouth. This feature is often exaggerated pretty heavily if you’ve ever had someone draw a caricature of you.

This trait starts to appear very early, around four weeks after conception. Our faces actually form from the sides first, with both halves unconnected until about week eight of development. Then the cells on both sides bridge the gap and form a connection.

When a person’s jaw is first being formed, the initial cleft in the chin is there too. The little furrow right in the middle of your chin can sometimes get more or less prominent over time depending on the person’s lifestyle. Sometimes losing or gaining weight can make the cleft look deeper or make the surrounding skin a bit tighter.

What actually causes cleft chin?

When scientists first studied chin shapes in families, they observed that it was very rare for two smooth-chinned parents to have a child with a chin dimple. Children with cleft chins almost always had at least one parent with the trait.1

From that, they predicted that a single gene determined chin shape. And that the cleft shape was dominant. Under this model, it would be impossible for a child to have a cleft chin if both parents had smooth ones.

But there are a few problems with this original line of thought. First, it’s totally possible for two smooth-chinned parents to have a cleft-chinned child. Plus, cleft chin doesn’t really follow the “either you have it or you don’t” pattern. If you think about it, the cleft doesn’t have to be super prominent. Chins come in all sorts of shapes and sizes! A large amount of variation is always a pretty good indicator that a trait is affected by more than a single gene.

Research on the cleft chin gene directly in people is a bit sparse, partly because it's a fairly innocuous trait that isn’t associated with any diseases. Chins generally are of more interest to dentists and anthropologists.

But if we add the tongue into the mix then things get a bit more interesting for geneticists. Genes that control tongue development also influence chin development.2 It turns out that these tongue and jaw genes also are linked to the ones for the roof of your mouth, and sometimes have a role in cleft palates and lips.3

Scientists have also looked at jaw formation in mice, which have a pretty similar set of expressed genes as us. If a gene called Msx1 isn’t fully expressed, mice end up with a cleft in their chin.4 It makes a bit of sense that a lot of genes for mouth development are linked so that the pieces can all fit together.

Chins are uniquely human, and if you happen to have a dimple in yours, then that makes you uniquely, you.

Read More:

-

Ancestry: Cleft chin

-

Ask-a-Geneticist: What genes cause cheek and chin dimples?

-

The Washington Independent: Cleft Chin: Genetics, Surgeries, and Myths

Author: Paul Markley

When this article was published in 2023, Paul was a PhD student in the Department of Biology, studying the ecological responses of arctic and alpine plants to anthropogenic climate change in Barnabas Daru’s lab. He wrote this article while in the Stanford at the Tech Program.

Skip Navigation

Skip Navigation