Is there a way to prevent a genetic condition from being passed on to a child?

January 24, 2020

- Related Topics:

- Medical genetics,

- Genetic conditions,

- Autosomal dominant inheritance

A concerned mom asks:

Andersen’s Syndrome has a 50/50 chance of being passed on from a parent to child. That’s the same chance as flipping a coin and landing on tails.

Andersen’s Syndrome is a genetic condition. It is caused when you inherit a non-working version of a specific gene from a parent.

It’s possible to screen newly fertilized embryos to see if a specific genetic change is present. Then the parents can choose which embryos to use for the pregnancy. This way, a couple may choose to prevent a specific genetic change from being inherited by their future children.

The best person to talk to about this would be your doctor or a genetic counselor. They are trained to help you understand how genetic conditions may run in your family, what that might mean for your children, and what your options are!

Where does this 50/50 chance come from?

Andersen’s Syndrome is an inherited, genetic condition. In most cases, it’s caused by a change in a single gene called KCNJ2.

In most people, this gene works just fine. KCNJ2 provides our bodies with instructions to make tiny gateways in our cells. Your cells have a lot of different kinds of gateways, which help them communicate with other cells and react to the world around them.

If your KCNJ2 gene doesn’t work properly, your muscle cells can’t communicate with each other very well. This can cause muscle weakness or issues with heart rhythm.

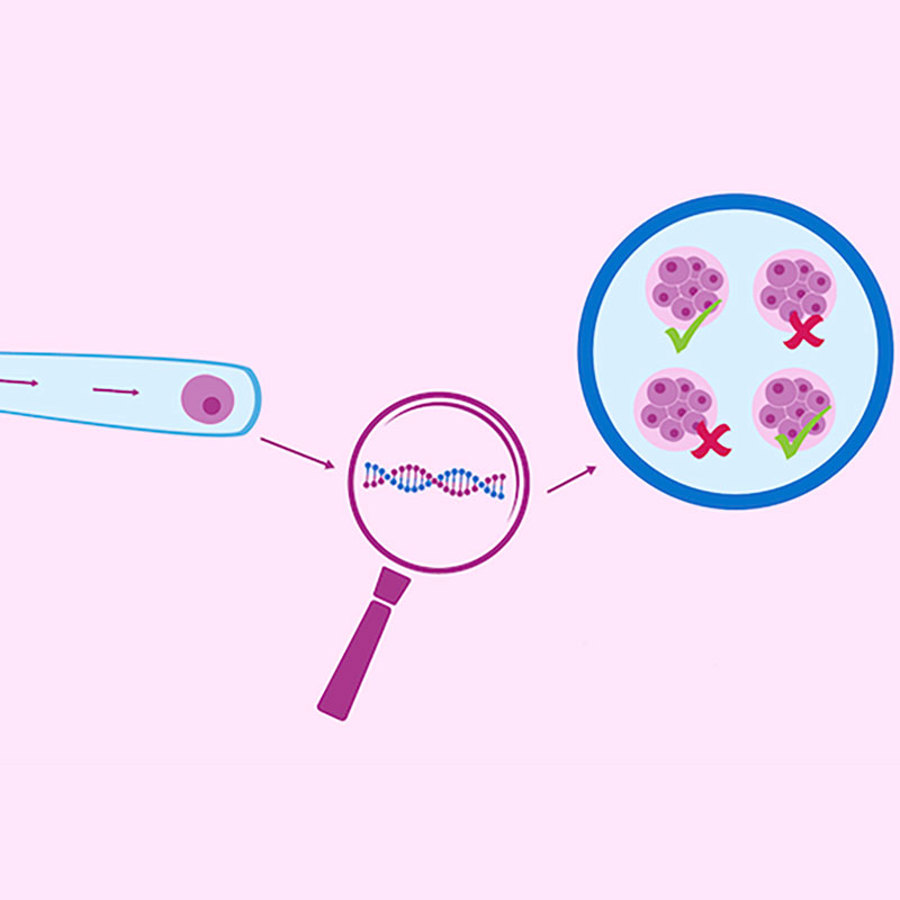

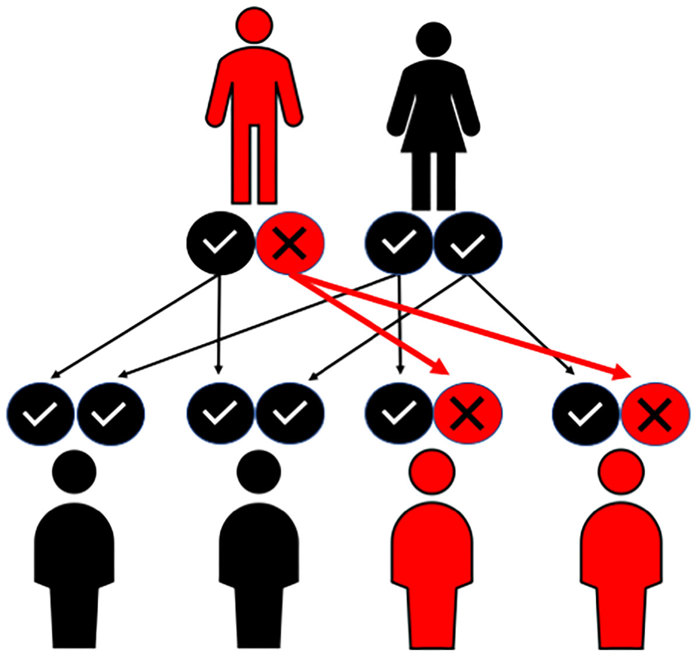

You may remember we have two copies of every gene. We inherit one from Mom, and the other from Dad!

If you inherit a single non-working copy of the KCNJ2 gene, you will develop Andersen’s Syndrome.

Your son inherited a working copy of the gene from you, and a broken copy from his father. And since just one non-working gene is enough to cause the disease, he developed Andersen’s Syndrome.

This is called an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern:

A person with a dominant genetic condition like this has a 50/50 chance of passing it on to any future child. This is the same chance as flipping a coin and getting tails.

Are there ways we can make this chance smaller?

There are new technologies that doctors can use to try to prevent a genetic condition from being passed on in families.

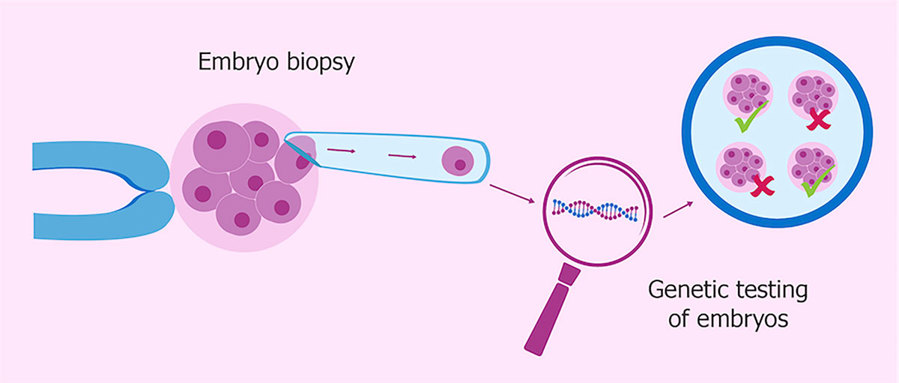

Testing for a genetic change is possible through a process called in vitro fertilization (IVF). In this process, a woman’s eggs are fertilized outside of the body. Then they are transferred into the woman when she is ready for pregnancy.

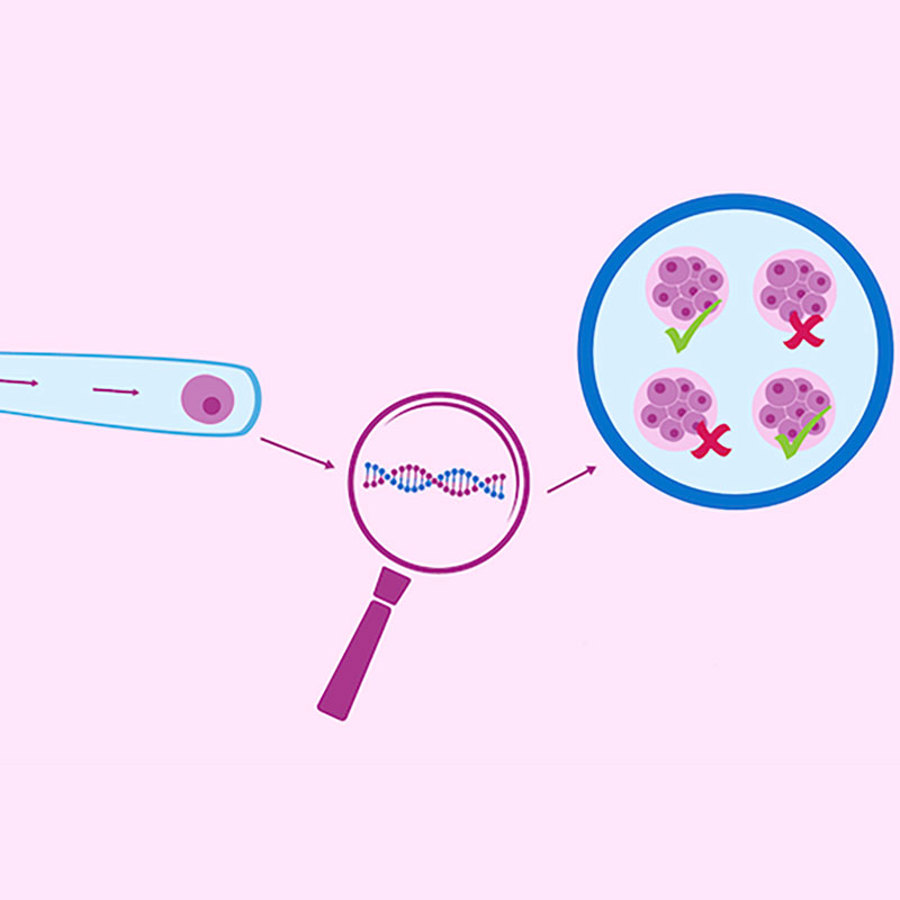

It’s possible to screen fertilized eggs before they are transferred to the mother. This is called preimplantation genetic diagnosis. Preimplantation genetic diagnosis can be used for many genetic conditions.

In this process, doctors take a biopsy (small sample) of a fertilized egg. Then they check to see if it has the genetic change of interest. For Andersen’s Syndrome, they would see if an embryo has the same change in the KCNJ2 gene as the parent.

If the genetic change is present, a couple can decide whether or not they would want to start a pregnancy with that embryo.

For example, if a couple does not want their future child to have Andersen’s Syndrome, they can choose an embryo that does not have KCNJ2 change.

Whether considering preimplantation diagnosis or not, a genetic counselor can help. Genetic counselors are trained to help you understand how genetic conditions may run in your family, what that might mean for your children, and what your options are.

You can find a genetic counselor in your area through the National Society of Genetic Counselor’s ‘Find a Genetic Counselor’ feature.

Author: Kathryn Reyes

When this answer was published in 2020, Kathryn was a student in the Stanford MS Program in Human Genetics and Genetic Counseling. She wrote this answer while participating in the Stanford at The Tech program.

Skip Navigation

Skip Navigation