Is it possible to generate a sperm cell from two individuals?

March 1, 2012

An undergraduate from California asks:

“Would it be possible to mix the DNA from multiple sperm cells, producing a single sperm cell with individual chromosomes from different males (say 16 from Male A, and 7 from Male B) and then combine this sperm with an egg?”

That’s an interesting question! Currently there’s no way we could pull this off. We certainly couldn’t just pluck out the chromosomes we want and stuff them back into a sperm.

Sperm cells are incredibly complex. Just like Humpty Dumpty, it would be almost impossible to take them apart and put them back together again.

And the sperm isn’t the only delicate part in all of this! The sperm’s twenty-three chromosomes are also very intricate.

They are inches long, super thin strands of DNA balled up in a specific way. With all that complex structure, it would be out of the question to just pluck the chromosomes out, pick the ones we want, and put them back together.

Plucking them out would damage them. Figuring out which ones we want would damage them. And putting them all back into a sperm would damage them again.

No, we’re going to have to take a different approach. Maybe we could fuse the cells of these two people and force the fused cell to split into two cells with the right number of chromosomes. Sort of like what happens when a sperm or egg cell gets made.

Next we’d have to pick the cells we want and turn them into sperm cells. Finally we'd pick the sperm cell with the right combination of chromosomes and fertilize an egg with it.

As you can tell, this isn’t going to be a walk in the park. But maybe something like this can be done someday in the future.

What I’ll do for the rest of the answer is go into a little more detail about why we can’t just pluck the chromosomes out. And then I’ll spend time on our little plan to create the Frankensteinian sperm.

Selecting the Right Sperm – What’s the Big Deal?

Conceptually, the easiest possibility is plucking the DNA we want and fertilizing an egg with it. Unfortunately, this is almost impossible.

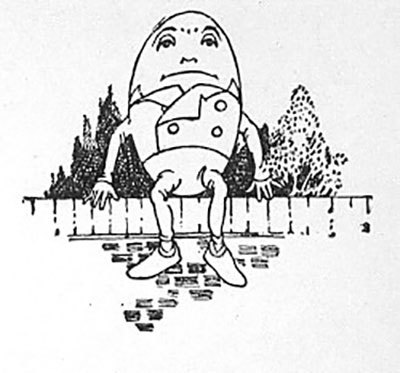

DNA is incredibly tiny – we need a very powerful microscope to even see it. And we can't really tell chromosomes apart by just looking at them under a microscope. They all look like DNA wound up into a finger-like structure. It’s only when the DNA is specially labeled that we can tell them apart.

One technique scientists use to tell one chromosome from another is called karyotyping. This is just a fancy term for dyeing the DNA so that each chromosome looks different.

Unfortunately dyeing the DNA destroys it. So if we were to use this technique to find the specific chromosomes we were interested in, we would end up with a heap of useless DNA.

One other way that chromosomes can be picked is by using new technology to get them out of a single cell. This method is called microfluidics, meaning “small amounts of fluid.”

Microfluidics works by first catching a single sperm cell. Next, we’d break the cell open and sort out the individual chromosomes using small amounts of fluid. We would then determine which chromosomes are which by looking for unique sections of DNA on each chromosome. By doing this we could separate the chromosomes we want from the ones we don’t.

But this technique damages the chromosomes too. And that doesn’t just mean the DNA.

Like thread on a spool, DNA is tightly wound around special proteins. These proteins give chromosomes their unique structure. Using either of these two methods would probably also damage the special proteins attached to the DNA.

Cell Fusion

OK, so we can’t pluck the DNA out. Let’s see if we can get the fusion technique to work.

Remember, we want to fuse the cells from the two people and get them to divide back into two cells with the right amount of DNA. Then we’d want to pick out the cells we want and turn them into sperm.

There isn’t any way right now to get a fused cell with 92 chromosomes to split into two cells with 46 chromosomes each. Normal cells can do this as an ordinary part of cell division. But we don’t know how to make a fused cell divide properly.

If we can get it to work, though, then things get much simpler. First we’d take the cells and let them divide over and over in a petri dish in the lab. We would start each dish from a single cell so each group of cells has the same DNA.

Then we could take a few out from each dish and see if they have the chromosomes we want. It is OK if we kill these cells as there are more back in the dish.

If we find what we're looking for, the next step is to turn them into sperm. Even though we can’t turn cells into sperm yet in humans, we can in mice.

Scientists use a special type of cell to artificially create cells that can make sperm in a lab, then implant these into infertile male mice. These mice are able to successfully have normal babies. So we’ll probably get it working in humans soon too.

Now we need to get the sperm into an egg. Luckily scientists are good at that! They can simply inject it directly into an egg using a procedure called intracytoplasmic sperm injection or ICSI. Scientists have been doing this for years as a fertility treatment.

Of course we still haven’t been able to do that first step. Without that, ICSI won’t do us any good in our efforts to conceive a child with DNA from two sperm and an egg. So it will be quite awhile before we can do anything like this ...

Read More:

- Penn Medicine: An animation of ICSI

- Fusing cells together

- Discover Magazine: Turning mouse cells into sperm

Author: Amy Johnson

When this answer was published in 2012, Amy was a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Biology, studying mammalian cell cycle control in Jan Skotheim’s laboratory. Amy wrote this answer while participating in the Stanford at The Tech program.

Skip Navigation

Skip Navigation