How do ancestry tests work?

July 9, 2018

- Related Topics:

- Ancestry,

- Ancestry tests,

- Consumer genetic testing,

- Genotyping

A curious adult from California asks:

“How do ancestry tests work?”

This is a great question! Ancestry tests are becoming really popular now, thanks to companies like 23andme, MyHeritage, and AncestryDNA (just to name a few). So, it’s good to ask the important question, how do they figure out where your ancestors are from just by checking out your saliva!?

Well, let’s start there. Typically with these ancestry tests, you’ll be asked to spit into a tube and mail it in to a company. Then, they extract your DNA from the cells in your saliva. And that’s where all the important information is, including ancestry.

There’s a lot of information in our DNA and not all of it is needed for an ancestry test

DNA is unique to each person. It’s like a blueprint, a map for who you are biologically. Your DNA blueprint is a string of four different letters: A, C, G, and T. And if you add up all the letters, it’s a 3 billion letter long code!

As you may know, you inherit a unique combination of half your mother’s DNA and half your father’s DNA. Since we all inherit DNA from our parents, we’re actually inheriting copies of DNA passed down from ancestors many generations ago.

What kind of information do you need to figure out your ancestry?

To do an ancestry test, you don’t need to know all 3 billion letters; you just need to know the code at a few hundred thousand particular locations. These are single spots in the DNA that scientists have determined can be different between different people.

Some of these differences mean you’ll have blonde hair instead of brown, or blue eyes instead of green. But at other spots, it doesn’t seem to matter much which version you have. It’s just a difference.

These differences can be very helpful for determining ancestry. Maybe at a particular spot most Europeans have a “T”, while Asians are more likely to have a “C”. By looking at thousands of these kinds of differences, we can start to predict where your ancestors came from.

Thousands of differences sounds like a lot, but it’s actually much less than 0.01% of your DNA.

There are differences between populations at certain locations in the DNA code

Today, it seems very common for people from different countries to meet and to have children. However, traveling 10,000 years ago wasn’t as easy as it is today!

That means that people within a certain area tended to share DNA. Because travel was hard, they were more likely to have children with someone who lived nearby. Over time, this caused people to be more closely related to their neighbors than with people who lived further away.

In an ancestry test, we’re zooming in on these similarities within populations, and differences between populations that live farther apart.

DNA from other people is used to figure out the ancestry test user’s “mystery” ancestry

So let’s get back to that tube of saliva you sent to an ancestry testing company. They’ll extract your DNA from the cells in your saliva and then look at what’s in your DNA at hundreds of thousands of places.

Once they have the DNA code at these locations, they can compare your DNA to a database of thousands of other people whose ancestry is known. Then they’ll see which group your DNA matches!

In some cases, parts of your DNA might match up with one population, and other parts might match up with another. This happens when you have ancestors from different parts of the world.

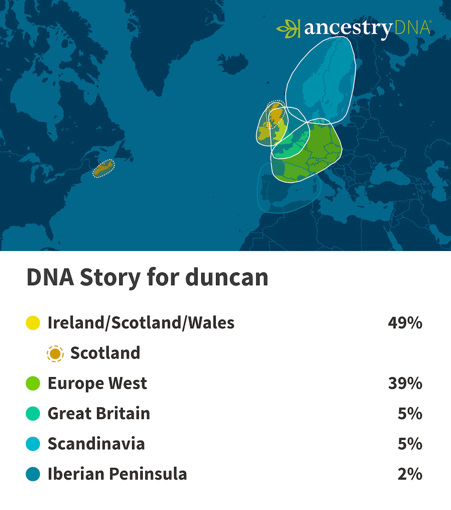

From the few spots in the DNA that the ancestry test analyzes, the total amount of DNA that matches each ancestry is added up and reported as percentages. For example, if you’re 30% Moroccan, that means that 30% of that your DNA matched specifically to DNA from other Moroccans in the company’s database.

Remember, ancestry tests only look at a very small percentage of your DNA in the first place. That means the 30% matching to Moroccans, for example, is still a very small fraction of your whole DNA code.

Ancestry test results aren’t 100% correct. They have their limitations

In general, it’s not difficult to get the continent correct (e.g. European or Asian). Ancestry assignments also tend to be more accurate for populations that are well-studied, like European populations.

In order for your ancestry to be correctly assigned, your ancestors need to be represented in the database the company is using as a reference. They can’t figure out your ancestor is from Malta if they don’t have someone from Malta to compare to!

The reference databases contain many people whose ancestry and genetic code is known. The company then compares your DNA to everyone in their database. They figure out which group (or groups!) you match best. A few things could be limiting here:

- The database doesn’t contain members of your ancestor’s population, so it just assigns your ancestry to a nearby, related population. Check out the list of populations your testing company uses to see if the people you think are your ancestors are included.

- Some populations share a lot of ancestry (e.g. England and Scotland) so it’s hard to tell if certain parts of your genome are English, Scottish, or from a population that lived there before the countries of England and Scotland even existed!

- It's hard to assign ancestry to a short piece of DNA. Remember, all humans are genetically very similar! Perhaps most people have an "A" at a specific location, while a handful of populations around the world are more likely to have a "T". That one position alone can't perfectly predict your ancestry. Instead, the prediction software needs to combine information from many nearby spots and find patterns. This gets tricky if you have a lot of mixed ancestry, each with very short pieces of DNA. It’s also tricky if the specific ancestry is from many generations ago -- since we only inherit 50% of one of our parent’s DNA, some ancestry could get randomly lost over time.

- Related to above, any predictions about small percentages of ancestry are usually not very confident results, often because of the first two reasons. You should check if there is a “confidence interval” option in the output results. Raising the confidence interval will narrow it down to the most confident results. (An example of this option in a 23andme report)

So as you can see there are a couple of limitations that can lead to inaccurate results. But, in general, the broader, continental ancestry estimates should be pretty accurate.

Ancestry is just a piece in the story of who you are and where you came from

Ancestry is just a small piece in the larger picture of who you are. An ancestry test will tell you where your ancestors originated, but it doesn’t tell you about their culture and experiences which may have been handed down for generations.

You might find out that your ancestry is mostly Chinese, for example. But that doesn’t tell the story of how your great-great-grandparents were involved with a small Indonesian community and passed down those traditions and culture to you. On the other hand, you could have ancestors from a small Greek community in Italy. Even though you always thought your ancestors were “Italian”, your ancestry will show that you’re Greek.

Our histories are complex and colorful. An ancestry test can be fun and interesting, but we can’t expect it to paint the picture perfectly. There are limitations to ancestry tests, so the colors don’t always turn out right. At the same time, it’s just a small piece of this bigger puzzle of who we are.

Read More:

- AncestryDNA: Unexpected ethnicity results

- LiveScience: I took 9 different DNA tests and here’s what I found

- How do paternity tests work?

Author: Margaret Antonio

When this answer was published in 2018, Margaret was a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Biomedical Informatics, studying population genomics in Jonathan Pritchard’s laboratory. She wrote this answer while participating in the Stanford at The Tech program.

Skip Navigation

Skip Navigation