What’s the difference between various types of ancestry tests?

January 22, 2026

- Related Topics:

- Consumer genetic testing,

- Ancestry,

- Ancestry tests,

- Mitochondria

A curious adult from California asks:

"What's the difference between maternal DNA tests, paternal DNA tests, and other ancestry tests?"

Ever wondered why your DNA tests give you different results? One test says your ancestors came from Italy, another traces your dad’s line to Scandinavia, and yet another shows a mix of continents you didn’t even expect. How can the same DNA tell so many different tales? Turns out the answer lies in how DNA is inherited – and what particular features of this inheritance your DNA test is looking at!

Maternal DNA tests follow your mother’s line through mitochondrial DNA, paternal DNA tests trace your father’s line through the Y chromosome, and autosomal DNA tests look at DNA from all your ancestors. Each test examines a different slice of your genome – and your heritage!

Autosomal DNA: The Full-Family Snapshot

Autosomal DNA refers to the 22 non-sex chromosomes that we inherit from both parents, giving us two copies of each autosome. Because half comes from your mother and half from your father, autosomal DNA captures contributions from all branches of your family tree. But here’s the twist: before autosomal DNA is passed down, it gets reshuffled through a process called recombination. That is, your parents do not just pass on one of their two copies of each chromosome–rather, sections of DNA from their two copies are exchanged with each other, creating a unique combination that you inherit.

Think of it like mixing two decks of cards every generation and dealing a new hand. Each hand contains pieces from all ancestors, but not necessarily every single one. That’s why autosomal DNA tests are best at detecting recent ancestry, giving broad ethnicity estimates, identifying close relatives, and showing which regions of the world contributed to your immediate family makeup.

So how do scientists actually perform an autosomal DNA test? The first step is collecting a DNA sample, usually from a cheek swab or saliva. Then, in the lab, scientists analyze hundreds to thousands of specific positions in your genome called single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). These are single-letter genetic variations that differ between people and populations. By comparing your pattern of SNPs to large reference databases of DNA from around the world, scientists can estimate your ethnic makeup and find relatives who share significant stretches of DNA with you.

The Y Chromosome: Tracing Down the Father’s Line

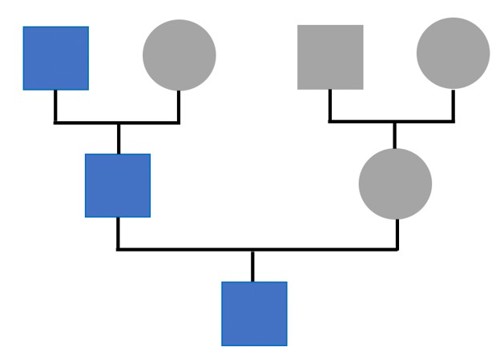

The Y chromosome is one of the two sex chromosomes and is passed down almost unchanged from biological father to son. Unlike autosomal DNA, the Y chromosome does not undergo recombination along most of its length (except in pseudoautosomal regions), meaning the sequence remains largely intact across generations. This makes it ideal for tracing a direct paternal line – from father to grandfather to great-grandfather and so on. Since only biological males have a Y chromosome, Y-DNA tests cannot be used to trace the paternal line of a biological female.

Because the Y chromosome is passed from biological father to son largely as a single unit, any mutations that arise on it are carried forward along that same paternal line. Over generations, these inherited changes create recognizable patterns that reflect shared father-to-son ancestry. These long-term patterns are grouped into what scientists call Y-chromosome haplogroups, which represent branches of the paternal family tree that have a shared set of inherited Y chromosome changes. By comparing haplogroups, scientists can determine whether two people share a recent paternal ancestor or whether their paternal lines split further back in time.

Just like autosomal DNA tests, Y DNA tests also look at SNPs to determine ancestry, but focus more on analyzing specific genomic regions called short tandem repeats (STRs). STRs are short DNA sequences that repeat multiple times in a row, but the number of repeats tends to vary between individuals. Because STRs change relatively frequently over generations,1 they are especially useful for distinguishing closely related paternal lines. By incorporating both STR and SNP data, Y-DNA tests can assign someone to a broad Y-chromosome haplogroup and also shed light on recent relationships along the father-son line.

Maternal Roots Revealed by Mitochondrial DNA

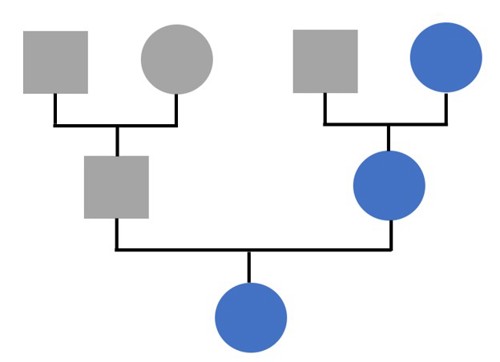

You might have heard that DNA is stored in the nucleus of the cell. But did you know that your cells also carry a tiny separate genome outside of your main DNA? This is mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), found in the mitochondria – the cell’s energy factories. Unlike the chromosomes in your nucleus, mtDNA is inherited exclusively from your mother, which means it follows a direct maternal line from mother to child, mother to grandchild, and so on.

Because mtDNA recombination events are very rare,2 mtDNA stays largely unchanged across generations. This makes it a perfect tool for tracing maternal ancestry, revealing patterns of ancestry from your mother’s line that autosomal or Y-DNA tests cannot capture. In particular, mtDNA test results allow individuals to be assigned to maternal haplogroups – shared lineages among people who descend from a common maternal ancestor.

mtDNA tests are performed by sequencing either the whole mitochondria genome or specific regions of it that tend to differ between maternal lineages. Because mtDNA exists in many copies per cell, it can be read even from small or degraded samples! And unlike Y-DNA tests, which can only be taken by biological males, anyone can take an mtDNA test to examine their maternal ancestry.

One Genome, Many Stories

Not all DNA tests are created equal! Each test looks at a different layer of your genome, revealing distinct lines of inheritance. Some are recent, some go back thousands of years, but taken together, they bring into focus a comprehensive view of your ancestry that no single test could ever show!

Author: Ronit Jain

When this article was published in 2026, Ronit was a graduate student in the Genetics Department at Stanford studying RNA-mediated gene regulatory processes. Ronit wrote this answer while participating in the Stanford at The Tech program.

Skip Navigation

Skip Navigation