Is diabetes a genetic disease?

January 3, 2006

- Related Topics:

- Complex traits,

- Environmental influence,

- Autoimmune disease,

- Medical genetics,

- Diabetes

An elementary school student from California asks:

"Is diabetes a genetic disease?"

Editor’s note (8/14/2021): While we know that there are genetic risk factors for diabetes, we still do not completely understand the exact genes involved. More recent studies have found that the genetic regions associated with diabetes could number in the hundreds.6

Genetics definitely plays a role in diabetes. But in most cases, it isn't the whole story.

Genetics usually affects how likely it is that someone will get diabetes. But whether they get it or not depends on what happens to them and/or what they do. “Nature” and “nurture” are both involved.

What is Diabetes?

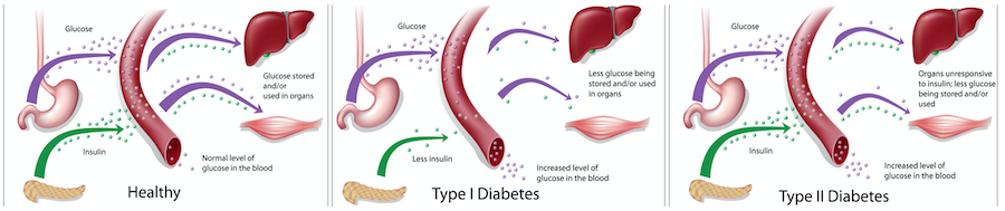

Before getting too far into what causes diabetes, let's back up and talk about what diabetes is. Diabetes is a disease where sugar builds up in the blood. If untreated, this extra sugar can cause damage to eyes, nerves, blood vessels, and kidneys.

Where does this sugar come from?

After you eat, your body breaks down food into a sugar called glucose. The glucose is then released into the blood to feed your cells. Normally, a protein called insulin helps to get the glucose into the cells so that it can be turned into energy.

In people with diabetes, something in this process goes wrong. Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disease, meaning that the body’s immune system attacks itself. In the case of type 1 diabetes, the immune system attacks the cells in the pancreas that make insulin. The end result is that the body doesn’t make enough insulin.

People with Type 2 diabetes don't use their insulin correctly. If you have too much sugar in your system for a long period of time, the cells in your body will stop using insulin to take in sugar. This is called insulin resistance, and causes extra sugar to build up in your bloodstream.

In both cases, people inherit differences in their DNA that increase their risk of getting diabetes.

Genetic Causes of Diabetes

So what genetic differences lead to Type 1 diabetes? One obvious difference would be one in or around the insulin gene itself*. This isn't that common, though. Most people with Type 1 diabetes have a normal insulin gene.

Other DNA differences can lead to an increased risk of getting Type 1 diabetes. For example, some people with Type 1 diabetes have differences in genes called HLA genes that normally help the immune system to work. Overall, there may be up to 18 areas of DNA where differences can increase your risk of getting Type 1 diabetes.1 Scientists are still trying to figure out what these are and how they work.

With Type 2 diabetes, the story is even less clear. In most cases, you need more than one DNA difference to get Type 2 diabetes. There could be up to 12 genes that have been shown to be involved in Type 2 diabetes, and there are probably more that scientists know nothing about yet.1

In most cases, having DNA differences isn't enough to make you diabetic — it can only increase your risk. To actually get diabetes, something else has to happen.

Non-genetic Causes of Diabetes

What is that something else? Researchers don't know yet. Early diet may be important.

Type 1 diabetes may be less common in people who were breastfed.2 Additionally, certain viral infections might be able to trigger Type 1 diabetes in some people.3

Type 2 diabetes is more common in overweight people or people who don't get enough exercise. The best thing you can do to prevent getting Type 2 diabetes is to eat healthy and get regular exercise.

A classic example of all of this is the Pima Indians of Arizona. A Pima Indian with diabetes was virtually unheard of for 2000 years or so.

Recently, many of them have adopted a more typical American lifestyle — little exercise and unhealthy food. Almost overnight, around half of the Pima Indians in Arizona ended up with Type 2 diabetes.4

Obviously their DNA didn't change that quickly. The DNA differences for increased Type 2 diabetes risk were always there.

But, with their old lifestyle, it didn't matter. In other words, their DNA wasn't enough to cause diabetes. Their environment had to change before they developed the disease.

Environment is important even if you are not a Pima Indian. Scientists know this by studying identical twins. Identical twins share the exact same DNA. So if some trait is completely due to DNA, then both identical twins would always share that trait.

But if identical twins don't always share the trait, then something besides DNA is also involved. In fact, if your identical twin has Type 1 diabetes, you likely have less than a 50% chance of getting it too. And if your identical twin has Type 2 diabetes, you can have up to a 75% chance of getting it.5 So DNA alone doesn't make you diabetic — environment is also important.

As you can see, the causes of diabetes are complicated. DNA, weight, physical activity, diet, and age all affect a person's risk of diabetes. No one thing alone can predict whether or not a person will get diabetes. This is good news if diabetes runs in your family; your DNA is not your destiny.

And if you or a loved one do have diabetes, treatments are becoming better and better all the time. With careful control of blood sugar, blood pressure, and weight, diabetics are now often able to live long and productive lives.

*Remember, genes are the instructions for making specific proteins. The insulin gene has the instructions for making insulin.

Author: Dr. Kim Matulef

When this answer was published in 2006, Kim was a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Molecular and Cellular Physiology, studying chloride ion channels and transporters in Merritt Maduke's laboratory. Kim wrote this answer while participating in the Stanford at The Tech program.

Skip Navigation

Skip Navigation