Can a person with a Y chromosome give birth to a child?

March 23, 2010

- Related Topics:

- Reproduction,

- Genetic sex,

- Rare events,

- Y chromosome

A curious adult from California asks:

"Can a person carrying a Y chromosome carry and give birth to a child?"

Yes, it is possible for someone with a Y chromosome to become pregnant and give birth to a child. But it's extremely rare.

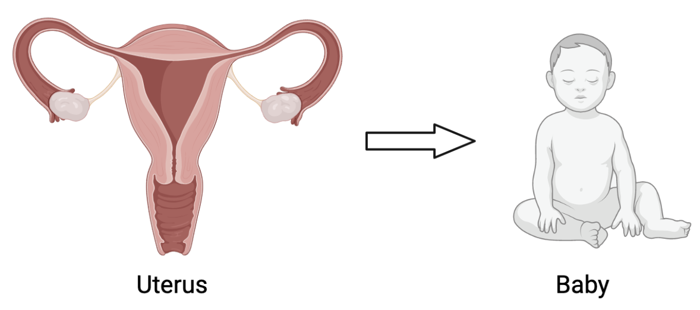

One of the most important requirements for pregnancy is having a uterus. Most people with a Y chromosome don't have a uterus and without one, there is no place for a baby to grow. No uterus, no pregnancy.

So how is it possible for people to have both a Y chromosome and a uterus? One possibility is that their Y chromosome lacks what it takes to make a male. Unfortunately, scientists don't know the rest of the story.

What we do know is that every once in a while, an XY person develops into a female. These individuals could be female in every way, but they almost always lack working ovaries and a uterus. Which means that they can't get pregnant.

For reasons we don't understand, on very rare occasions, an XY female does have a uterus. But she still needs a donated egg, since she can't make one herself (no ovaries).

There are a handful of cases where individuals with a Y chromosome, a uterus, and a donated egg have become pregnant and given birth to a child. One such mom even had twins!

What I thought I'd do for the rest of the article is talk about why having a Y chromosome almost always keeps someone from having a uterus. Then I'll also go over some natural conditions people have where they look female but have a Y chromosome.

The Y Chromosome Almost Always Makes a Male

The sex chromosomes are what make us male or female. Well, to be more accurate, certain genes on the Y chromosome can start the process of making a male. Other genes are then needed to complete the process.

Remember, a gene is just a piece of DNA with the instructions for making a protein. And the protein is what goes out and gets a job done.

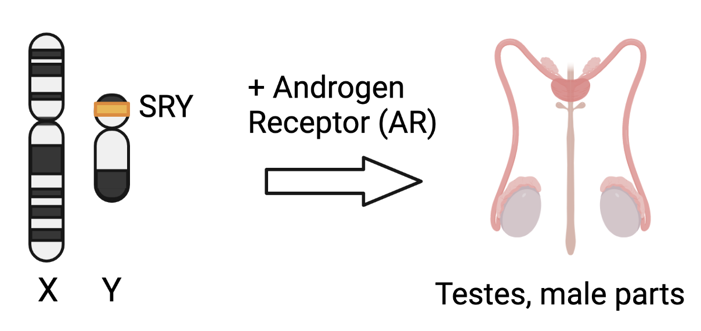

For example, the Y chromosome has a gene on it called SRY (Sex-determining Region-Y). Because it is on the Y, usually only men have this gene.

SRY is important in getting the ball rolling on making testes. And testes are important for making lots of testosterone and other androgens.

The testosterone then goes on to finish the job of making male parts. But testosterone doesn't do this on its own. It needs to work with a certain protein called the androgen receptor (AR).

Testosterone and AR pair up to turn lots of different genes on and off. The pattern of genes that are ultimately on makes a fertile male.

Since most females don't have a Y chromosome, there is no SRY gene to trigger male development. Instead of making testes, females develop ovaries. And they make lots of estrogen instead of testosterone.

The estrogen pairs up with the estrogen receptor (ER) to turn a different set of genes on and off. This pattern of genes leads to a uterus, ovaries, and the other parts of a fertile female.

So to end up a fertile male, you need working SRY and AR genes. To end up a fertile female, you need for the SRY gene to be absent and for the ER gene to work right*.

(*This is of course a gross oversimplification. Lots of other genes are needed to make a fertile male and female.)

Sometimes the Y Chromosome Doesn't Make a Male

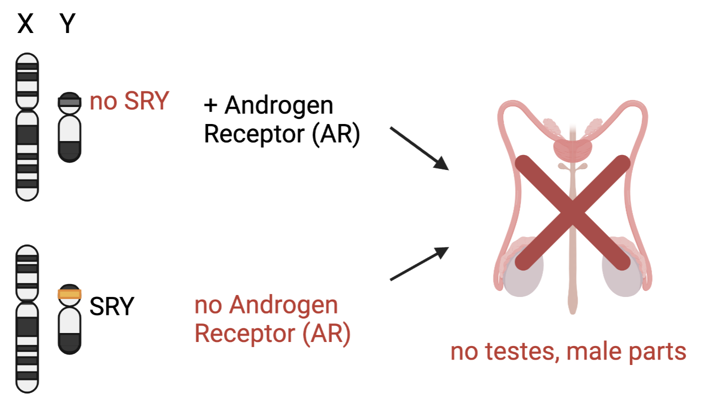

Both the SRY and the AR genes can stop working properly. When this happens, the male parts don't get made. But neither do the ovaries or uterus, in most cases. The end result is an XY person who looks female but almost always cannot get pregnant.

When the SRY gene isn't working, the resulting condition is called Swyer syndrome, or XY gonadal dysgenesis. Individuals with this condition are genetically male (XY), but look female.

There are also XY females who have a working SRY gene on the Y chromosome. However, they have a broken or missing AR gene. This gene normally makes androgen receptor. But if the gene is broken, androgen receptor isn't made.

Without androgen receptor, cells don't respond to androgens or testosterone. This means that the cells won't receive the message to make male anatomy. This condition is called complete androgen insensitivity syndrome (CAIS).

One of the few differences between XX females and XY females is that nearly all XY females don't have ovaries and a uterus. Instead, XY females typically have undeveloped testes inside their bodies. As I mentioned before, in very rare cases, an XY female does have a uterus. Scientists still don't know how this happens. But for these rare individuals, having a Y chromosome and becoming pregnant is possible.

Male Pregnancy in the News

If you've spent some time on the Internet or watching TV, you may think it's possible for males to become pregnant. Don't believe everything you see and read!

It is true that a man has given birth to two children in the last few years. But this man was born a woman and has no Y chromosome. He simply opted to keep his uterus when he had his sex reassignment surgery.

Other reports have turned out to be hoaxes. So unless you're a seahorse, if you have a Y chromosome and lack a uterus, you can't get pregnant.

Here's the bottom line: pregnancy requires a uterus.

Males and most XY females cannot become pregnant because they don't have a uterus. The uterus is where the fetus develops, and pregnancy isn't possible without it.

In most cases, having a Y chromosome means having no uterus, so pregnancy isn't possible. But for the very few XY females who have a uterus, pregnancy started with a donated egg is possible.

Author: Karen Colbert

When this answer was published in 2010, Karen was a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Structural Biology, studying the molecular basis of neurotransmission in Willliam Weis' laboratory. Karen wrote this answer while participating in the Stanford at The Tech program.

Skip Navigation

Skip Navigation