What are the chances of having Huntington’s, if a great uncle has it?

March 4, 2015

- Related Topics:

- Genetic conditions,

- Autosomal dominant inheritance,

- Medical genetics

A curious adult from Iowa asks:

"A friend of mine just told me his great uncle was diagnosed with Huntington’s disease? What are his chances for having the disease? And what about his son?"

This is a trickier question than you might think. With dominant diseases like Huntington’s Disease (HD), it is usually pretty easy to figure out risks. Generally if one parent has it then each child has a 50% chance of having it too.

And if neither parent has the disease, then odds are that none of the kids will either. Huntington’s is a dominant genetic disease. With these diseases, you are almost never an invisible carrier like you can be with recessive genetic diseases. You usually can’t pass on a gene that causes the disease because you don’t have it.

So if the great uncle had HD but your friend’s grandparents didn’t, then we’d say he couldn’t have it. After all, if the grandparents don’t have the disease, then they don’t have the gene. Which of course means they can’t pass it to your friend’s parents!

But HD is complicated by the fact that it often doesn’t kick in until someone is in their 50’s. If a parent with the condition happened to pass away from other causes before the symptoms appeared, then they might have passed the disease on. In these cases you can have a chance to have the disease even if neither of your parents showed any symptoms.

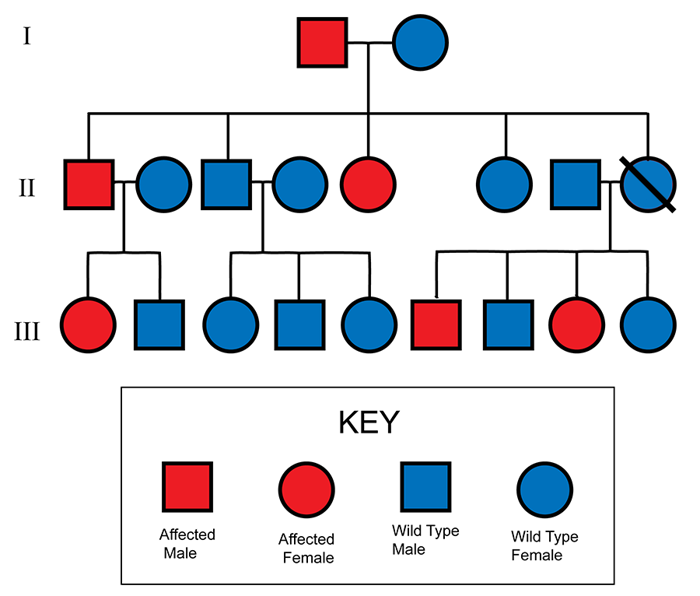

Here is what that sort of family tree might look like:

In this family, it looks like the mother and father on the far right in the second generation have two kids with the disease even though neither parent had it. Most likely this is because the mom passed away before her symptoms became apparent (the slash indicates she has passed away). Most likely her kids got HD from her.

What this all means is that if your friend’s grandparents lived to a ripe old age without the disease, then the odds are pretty good your friend doesn’t have the gene. The same is true if your friend’s parents are in their 60’s without the disease.

Fortunately for the people who want to know for sure, there is a genetic test that can look for the DNA differences that can lead to HD. A doctor or genetic counselor can help someone get that type of test!

Where the 50% Number Comes From

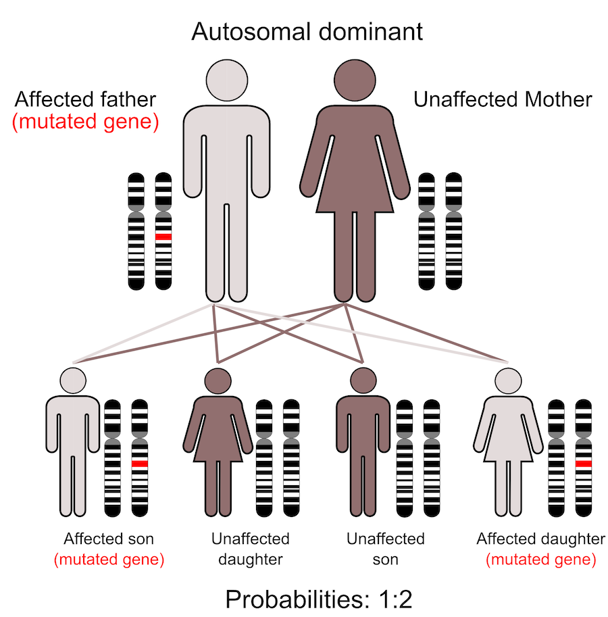

You get HD if you have a broken version of a specific gene. Since you get your genes from your parents, a common way to get the disease is to inherit a broken copy of the gene from them.

As I mentioned, HD is a dominantly inherited disease. This means that if one of your parents has the disease, you have a 50% chance of getting it from them. And if your parents don’t have the disease, you probably won’t get it. Let’s look more closely at why.

Everyone has two copies of each gene. You get one of your mom’s copies and one of your dad’s copies. Sadly you don’t get to pick which one.

So let’s say your dad has HD and your mom doesn’t. Your mom has two good copies of the gene, so whichever one you get from her will work just fine.

But your dad has one broken copy of the gene and one good copy. You will get one of them randomly, so your chances of getting the broken copy are one in two or 50%. It’s just like the chance of getting tails if you flip a coin.

The good news is that if you don’t get the broken copy of the gene, then you can’t pass the disease on to your children. And even if you do have it, your kids only have a 50% chance of getting it from you.

If you do have a broken gene, there is a way to make sure your kids don’t have it. It’s called preimplantation genetic diagnosis, or PGD.

Scientists do PGD by fertilizing an egg outside of a mother just like in vitro fertilization (IVF). Once the embryo grows a little, they can use a small part of it to test for the broken gene. If the embryo has the broken gene, they won’t implant it back into the mother, so she won’t have a child with the disease.

A Tangled Problem

Not all diseases are dominant like HD. Many genetic diseases only happen when both copies of a gene are broken or lost.

But HD is different. One broken copy is enough to cause the disease.

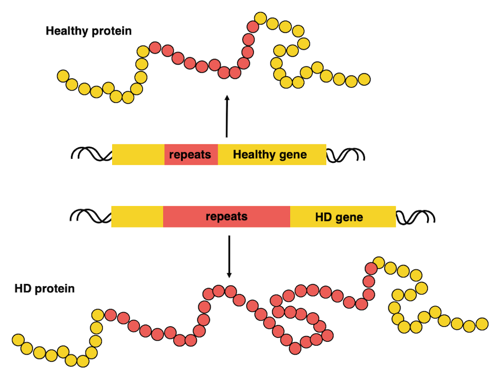

Each gene has the instructions for making a specific protein. And each protein has a specific job to do in the cell. In this case, the huntingtin gene has the instructions for making the huntingtin protein.

Genetic diseases often happen when a DNA change messes up the instructions in a gene. Now the protein the gene codes for is broken and can’t do its job.

Sometimes the protein simply stops working and other times it gains some new function. In HD, the huntingtin protein does something it shouldn’t.

In HD, a part of the huntingtin gene repeats itself over and over. This causes a longer form of the huntingtin protein to get made. And this long protein gets tangled up with many of the other proteins in the cell.

This causes bunches of other proteins to stick together and stops all of them from doing their job in the cell. Eventually the cells die because so many things are not working. This is what causes the symptoms of HD.

So losing a gene doesn’t cause HD. Instead it is caused by gaining a longer protein that stops everything else from working.

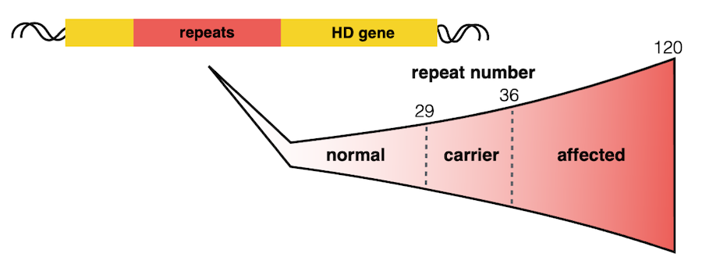

But not everyone with HD has the same length of extra protein. And this makes HD an even more complicated disease.

The HD Gray Area

As I mentioned before, it is possible to get HD even if your parents don’t have it. If your parent passes away before showing symptoms of HD, you might not know whether they had a broken HD gene.

Although this doesn’t apply to your case, there is another way that you can get HD even if both of your parents live long and healthy lives. It has to do with the fact that different people have different lengths of the huntingtin protein. And the same length protein can have different effects in different people.

There are certain lengths of the huntingtin protein that are safe for everyone and certain lengths that cause anyone who has them to end up with HD. But there are in between lengths that are tricky. Even the same length protein can cause HD in one person but not someone else.

So you can imagine a parent with one of these intermediate length proteins. She happens to have the right genetic background so that her cells can deal with this slightly longer protein.

Now imagine she passes it down to her son whose cells can’t deal with a protein that long. He ends up with HD even though his mom did not have any symptoms. And this isn’t the only way these slightly longer proteins can cause problems.

When healthy people with slightly longer proteins pass the gene on to their child, it sometimes gets a little bit longer. And this can sometimes make it long enough to cause the disease. So then the child gets HD even when neither parent did.

So even if you get a genetic test to know for sure what your HD gene is like, there can still be some uncertainty about whether you will get HD. Which is why such a seemingly simple question needed such a long answer!

Author: Anne Sapiro

When this answer was published in 2015, Anne was a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Genetics, studying regulation of mRNA processing in Billy Li’s laboratory. She wrote this answer while participating in the Stanford at The Tech program.

Skip Navigation

Skip Navigation