How do I know if I’m a secretor or a non-secretor?

May 29, 2019

- Related Topics:

- Blood type,

- Complex traits,

- ABO blood type

A curious adult from Georgia asks:

“How can I figure out if I am a secretor or non-secretor? What does this mean in everyday life?”

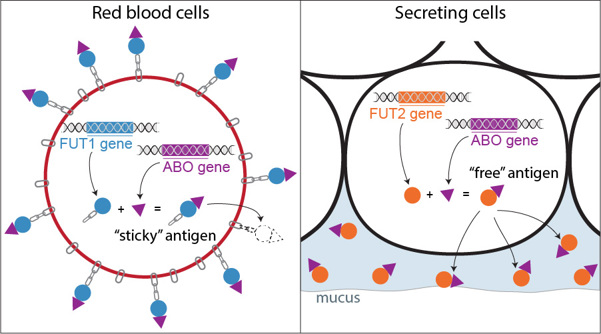

If you’re a secretor, it means that your ABO blood type (A, B, AB, or O) is not only in your blood, but also in other body fluids like saliva and mucus. Whether you’re a secretor or not is caused by one particular gene, which you can figure out with DNA testing kits.

We actually don’t know much about how our “secretor status” affects everyday life. The most I can say is that it has been linked to some disease risks, which I’ll get into below!

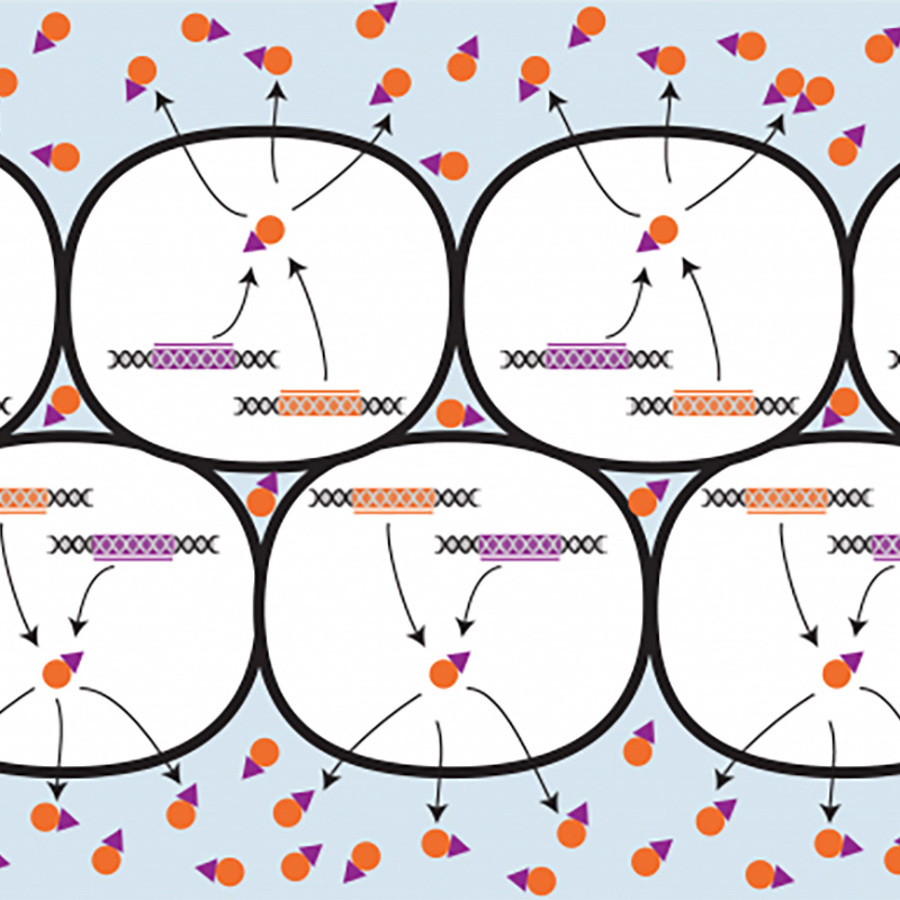

A primer on blood type

When we talk about ABO blood types, we’re talking about different types of sugars that are stuck to the surface of red blood cells. These sugars are called antigens.

Our ABO blood type comes from a stretch of DNA (called the ABO gene) that has the instructions to make these different sugars. Depending on which instructions your DNA has, you’ll make a certain combination of these antigens - this creates your blood type!

If you’re interested in how we inherit our ABO blood type, take a look at this post.

Taking your blood type beyond your blood cells

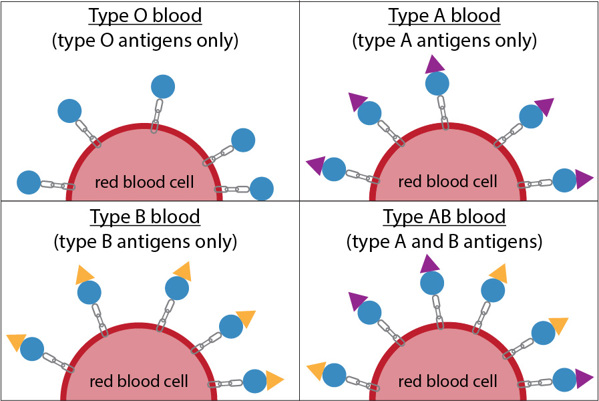

But here’s a twist: our blood cells aren’t the only cells reading the ABO gene. There are other parts of our body that can make these antigens too!

When red blood cells make antigens, they also need to read a gene called FUT1. Together, ABO and FUT1 make a “sticky” antigen. This antigen attaches to the surface of the red blood cells.

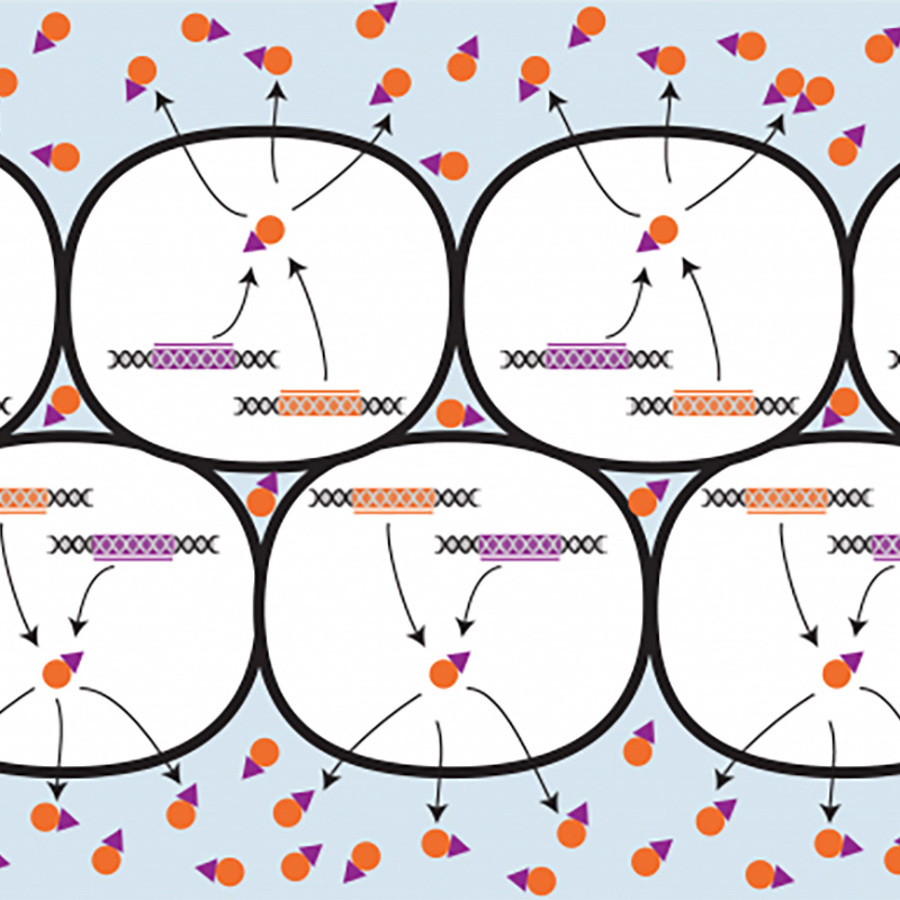

But when other cells make antigens, they read a different gene called FUT2. Together, ABO and FUT2 make a “soluble” antigen. This means the antigens can float around on their own – they don’t need to be stuck to a cell’s surface.

So what are these other cells that read FUT2? They’re any cells that make some type of body fluid. This includes the cells in our skin that make sweat, the cells in our mouth that make saliva, and the cells in our airway and digestive system that make mucus.

Around 80% of people are secretors.1 For the other 20% who are non-secretors, their FUT2 gene has been interrupted by a mutation, so they can’t make the free-floating form of antigens.

So if you’re a secretor, there are cells in your mouth that release your blood-type antigens into saliva. And there are cells in your tear ducts that release your antigens into tears. And so on, for all of the fluids that your body makes!

Your blood type and your secretor status are independent, since they come from two separate genes (ABO and FUT2). So for example, being blood type A does not affect your chance of being a secretor.

Your secretor status might affect some immune responses

Figuring out the role our secretor status plays in our lives is tricky, especially when we still don’t even know how our blood type itself affects our health!

That said, there is a little bit of research that suggests that being a secretor (or not) affects how we respond to some infections.

Before I get into it, I should say that most of these results have only been found once or twice. To be sure of the effect of any gene, studies need to be repeated. We want to make sure we get the same results in many different groups of people before we get too excited!

Okay, with that disclaimer out of the way, here are some of the trends we see with secretor status:

Non-secretors seem to be less likely to get some stomach illnesses, like stomach flu and ulcers.2-4 The case is strongest for stomach flu: in those studies, all of the people who got sick were secretors, and none of them were non-secretors!

On the flip side, non-secretors seem to be more likely to get yeast infections.5 They also seem to be more likely to get pneumonia and meningitis.6,7

Being a non-secretor has also been connected to some autoimmune diseases. The link between being a non-secretor and having inflammatory bowel disease has the most support. But, there are also links between being a non-secretor and having psoriasis or type 1 diabetes.8-11

Is there a diet for your blood type?

When I was looking for information to help me answer this question, lots of websites popped up that were related to blood type diets. These are fad diets where you get lists of foods to eat and avoid, depending on your blood type and whether or not you’re a secretor.

Blood type diets are based on the idea that our ABO blood type and secretor status affect how we digest food. Although this is a really interesting idea, and it might even be true, right now there is no research showing that these diets work.

On the one hand, our secretor status has been linked to the bacteria that are living in our intestines. This is because some bacteria like to bind to or eat the blood-type sugars made in the intestine by secretors.

The bacteria in our intestines help us break down food and produce certain nutrients that we can’t make on our own. So, it actually makes a lot of sense that our secretor status could affect digestion.

But on the other hand, none of these diet companies have tested how well their products work on the people using them. Not only that, but independent studies have failed to get results when testing out these diets.12,13

This means that we still don’t really understand how our secretor status could affect digestion - so any diets built around this idea are missing some really important information.

Needless to say, I won’t be signing up for a blood type diet any time soon!

Ways of learning your secretor status

Even though knowing your secretor status probably won’t affect the choices you make every day, it’s still cool to learn more about our bodies and how they work!

You can figure out whether or not you’re a secretor through DNA testing. Some companies offer kits just for secretor status, but if you want more genetic bang for your buck you can figure it out from 23andMe results!

23andMe provides info on a genetic variant called rs601338, which is in the FUT2 gene. If you’re an ‘AA’, you’re a non-secretor. If you’re a ‘GA’ or ‘GG’, you’re a secretor.

Read More:

- There’s tons of information about the ABO blood groups here.

- Why the Blood-Type Diet is a Dangerous Myth is a criticism of the Blood Type Diet from someone who actually tried it out.

- An early clue in the Golden State Killer case was that the perpetrator was a non-secretor. This helped police eliminate a lot of suspects! Read more on the GSK in this book.

Author: Olivia de Goede

When this answer was published in 2019, Olivia was a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Genetics, studying long non-coding RNAs in the immune system in both Karla Kirkegaard’s and Stephen Montgomery’s laboratories. She wrote this answer while participating in the Stanford at The Tech program.

Skip Navigation

Skip Navigation