Why are females always carriers for X-linked diseases, and not affected by X-inactivation?

March 7, 2019

- Related Topics:

- X linked inheritance,

- Genetic conditions,

- Carrier,

- X inactivation

An undergraduate student from Egypt asks:

"In X-linked recessive diseases, why are females who inherit only 1 disease-causing allele carriers, since 1 of the 2 chromosomes is inactivated? What if the chromosome with the normal allele is the one that is inactivated, and the other disease-causing allele is the active one? Why isn’t X-inactivation taken into consideration? Why are females always carriers, and not affected by chance depending on which X chromosome is inactivated?"

Actually, some women who carry X-linked recessive conditions do have symptoms, and X-inactivation can play a role in this.

But before I get into how that happens, let’s look at how X-inactivation works.

Why does X-inactivation happen?

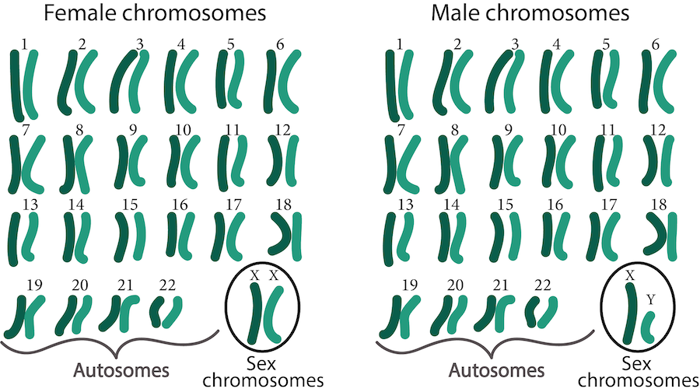

Most genetic information is the same for males and females. Usually, humans have 23 pairs of chromosomes in their cells. Of these, 22 pairs are the same between men and women.

The difference comes in the last pair of chromosomes. These are also called the sex chromosomes.

- Most men are XY: one X chromosome from Mom and one Y chromosome from Dad.

- Most women are XX: one X chromosome inherited from each parent.

We only need the information from one X-chromosome to survive. After all, men only have one X-chromosome!

But women have two X-chromosomes. If both of the X-chromosomes were active, there would be an overload of information from the X-chromosome.

If you think of genetic information like a recipe, you can see how having some instructions doubled could be a problem.

Imagine you’re making a cake and you repeat a section of the instructions. If you use twice as much flour, your cake probably won’t turn out the way you planned! In the same way, having twice as much information from the X-chromosome could cause a problem.

X-inactivation solves this problem. Nearly every cell in a woman’s body shuts down one X-chromosome, leaving just one working version.

How does X-inactivation work?

Soon after an egg is fertilized, each cell in the new embryo randomly puts one X-chromosome into a dormant state.

Once a cell puts an X-chromosome out of commission, it sticks to that decision. Every new cell that comes from it will inactivate the same chromosome.

The inactive X-chromosome is packed into a small ball and shuffled to the side of the cell. The chromosome is squished so tightly that the cell can’t use it at all – it’s completely inactivated.

Humans don’t have any obvious signs that show which X-chromosome is active in each cell. But in cats, you can actually see where each X-chromosome is active.

One of the genes for feline fur color is located on the X-chromosome. A female cat with different color genes on each of her X chromosomes will have tortoiseshell fur! These patches of black and orange hair let you actually see where each X chromosome is active.

We expect that around half of a woman’s cells will use one X-chromosome and half will use the other. However, it isn’t always that simple!

Sometimes we see that nearly all of a woman’s cells have inactivated the same X-chromosome. There are a few different theories for why this could happen:

- More cells may have randomly chosen to turn off the same chromosome.

- Cells might recognize a problem with one X-chromosome and inactivate the damaged one more often.

- Cells using one X-chromosome might not survive as well, causing cells expressing the other to be more common.

There are other possibilities as well! Researchers are trying to learn more about how X-inactivation works.

So what does this mean for women who carry X-linked genetic changes?

In general, women aren’t affected by X-linked conditions. That’s because X-linked conditions are usually caused when you don’t have any working copies of a gene on the X-chromosome.

Men only have one X-chromosome to begin with. So they only need one non-working (or mutated) gene to show symptoms of an X-linked condition.

But, women have an extra X-chromosome! Even if a woman has a mutation on one X-chromosome, she’ll probably have a working version on the other chromosome. Usually, enough of a woman’s cells express the working version of the gene to keep her healthy.

However, there are some women who have symptoms of X-linked conditions. Often women who have symptoms are more mildly affected than their male relatives. That’s because they have the working copy of X-chromosome helping out.

But it is possible for women to be nearly as severely affected as males. Women who have more severe symptoms may simply have more cells that inactivated the healthy X-chromosome.

It can be difficult for female carriers who want to know if they will eventually develop symptoms. Doctors may consider testing some of a woman’s cells to see which X-chromosome is more commonly inactivated.

However, this doesn’t always predict which women will develop symptoms. There are different patterns of X-inactivation throughout the body and we can’t test every cell!

Whether or not a female carrier has symptoms, she can pass the non-working X-chromosome on to children. People who think they could be at risk for having (or carrying) an X-linked condition should consider speaking to a doctor or genetic counselor. To learn more about genetic counseling or to find a genetic counselor in your area, visit http://nsgc.org.

Read More:

-

Carriers of Duchenne muscular dystrophy can show some disease symptoms.

-

Do you have a tortoiseshell or calico cat? Learn more about cat color genetics!

Author: Brita Christenson

When this answer was published in 2019, Brita was a student in the Stanford MS Program in Human Genetics and Genetic Counseling. She wrote this answer while participating in the Stanford at The Tech program.

Skip Navigation

Skip Navigation