Why don’t I have freckles while my parents and brother and various aunts and uncles do?

December 8, 2009

- Related Topics:

- Pigmentation traits,

- Skin pigmentation,

- Freckles,

- Dominant and recessive,

- Red hair

A high school student from California asks:

"Why don’t I have freckles while my parents and brother and various aunts and uncles do?"

Freckles are caused by two things - the sun and genes. So unless you've been living in a cave your whole life, you must have a different set of genes than your other relatives do.

Your parents, aunts, uncles, and brother have freckles because they carry a gene for them. You don't have freckles because you don't have this particular gene.

It might seem confusing that you ended up with different genes from your brother since you both have the same parents. To understand how this happened, you need to know four things:

- We have two copies of each of our genes, one from mom and one from dad.

- Genes can come in different versions.

- Parents only pass one of their copies down to their children.

- Which copy gets passed down is totally random.

Let's use these four facts to explain why you don't have freckles. And why your brother does.

The MC1R Gene and Freckles

The main gene responsible for freckles is called MC1R. It comes in two different versions, freckle (F) and non-freckle (f).

Like most other genes, we each have two copies of MC1R. Whether or not you have freckles depends on the combination of the freckle (F) and non-freckle (f) versions of MC1R you have.

Both FF and Ff people have freckles. What this means is that anyone with at least one copy of the freckle version (F) will have freckles.

This is why having freckles is a dominant trait. The freckle version dominates the non-freckle one.

Most likely your parents are both Ff. They have one copy of each version of the MC1R gene.

Your parents each passed you an f, meaning you ended up with ff. Since you didn't get a freckle version (F), you don't have freckles.

On the other hand, your brother must have gotten at least one F from one of your parents. That makes him either Ff or FF and so he has freckles. Because F is dominant over f.

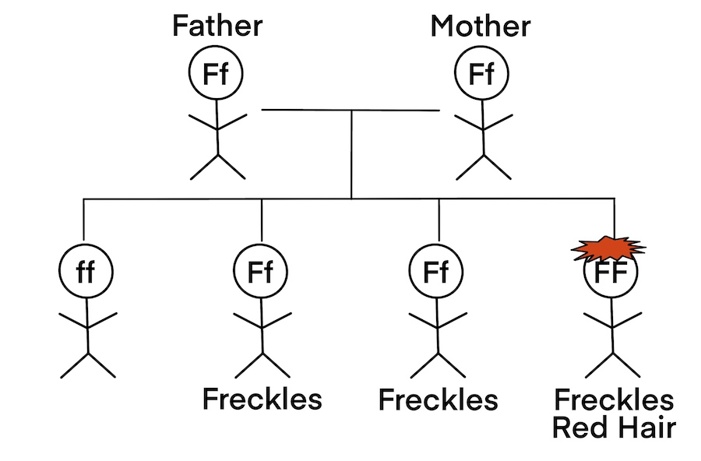

To show you better how this works, I've drawn out your parents MC1R genes and the three different possibilities for their children in the image below. As I said, your parents are Ff and so have freckles.

As you can see, each child has a 1 in 4 chance of being ff and not ending up with freckles. This is you!

Each child also has a 2 in 4 (or 1 in 2) chance of ending up Ff. These kids will have freckles.

Finally, each child has a 1 in 4 chance of ending up FF. Not only will they have freckles, but they'll probably have red hair too!

Now, if your brother only has freckles, there's a good chance he is Ff. But if he has both freckles and red hair, he's most likely FF.

It turns out that the MC1R gene is also responsible for red hair. People with red hair have two copies of the freckle version of the MC1R gene (FF). And because they have at least one F, many times people with red hair also have freckles.

So there you have it. People with freckles like your relatives have at least one copy of the F version of the MC1R gene. Since you got an f version from each parent, you don't have freckles.

What I thought I'd do for the rest of the answer is go over what freckles are and how the F version of the MC1R gene causes them. From this explanation it'll become clear why people with two F versions (FF) have red hair.

A Natural Sun Block

Freckles appear as dark spots on the skin because they contain a pigment called melanin. Our bodies make melanin to protect us from the harsh rays of the sun. Melanin blocks the sun's ultraviolet (UV) rays to prevent sunburn and skin cancer.

Only special cells in our skin, called melanocytes, can make melanin. People with melanocytes distributed evenly throughout the skin get tan from the sun.

People with freckles have melanocytes clumped together. After being in the sun, they get dark spots on the skin instead of an even tan. This explains why freckles are usually more noticeable in the summer and tend to fade in the winter.

Freckles Happen When MC1R Can't Do Its Job

As I said at the beginning, the MC1R gene is involved in freckles. To understand how, we need to dig a bit deeper into what a gene is.

Remember genes are the instructions for life. Each gene has the instructions for making a single protein and each of these proteins does a specific job in the body.

So the MC1R gene has the instructions for making a specific protein -- the MC1R protein. This protein is stuck on the outside of melanocytes where it acts kind of like a watchdog. When it senses signals from UV rays, it alerts the melanocyte to make melanin. This melanin protects us from the sun.

There isn't just one kind of melanin. It comes in two forms -- eumelanin and pheomelanin. One of the jobs of the MC1R protein is to change pheomelanin into eumelanin.

People with freckles tend to have a version of the MC1R protein that can't do this job very well. Their melanocytes are clustered together and they have more pheomelanin than usual.

At this point you may have guessed that the pigment pheomelanin is red. This is why freckles are usually orangish-red in color. And why people with two freckle versions (FF) of the MC1R gene have red hair. They have a build up of pheomelanin in their hair.

Not everyone with one or two copies of the freckle MC1R gene ends up getting freckles. And not everyone with red hair has freckles. This suggests that there is more to freckling than just the MC1R gene. Most likely, there are other genes involved. Scientists are actively trying to figure out what they are and how they interact with MC1R.

Read More:

Author: Gwen Liu

When this answer was published in 2009, Gwen was a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Microbiology & Immunology, studying the structure and function of microrna genes in Chang-Zhen Chen’s laboratory. Gwen wrote this answer while participating in the Stanford at The Tech program.

Skip Navigation

Skip Navigation