Are any people genetically predisposed to being immune to HIV?

November 19, 2009

- Related Topics:

- Genetic variation,

- Microbiology,

- Gene expression,

- Genes to proteins,

- Medical genetics,

- Molecular biology

An undergraduate student from California asks:

As far as we know, no one is immune to HIV infection. But some people do have genes that make this virus’ job harder.

These people are definitely less likely to be infected by HIV. And when they do get infected, they tend to develop AIDS symptoms more slowly as well.

An HIV infection starts when the virus attaches itself to special receptors on the outside of certain blood cells. The virus then injects its RNA into the cell and forces the cell to make new virus. These viruses eventually destroy the cell they’re in and go out and repeat the process. When there are few of these cells left and lots of virus, AIDS develops.

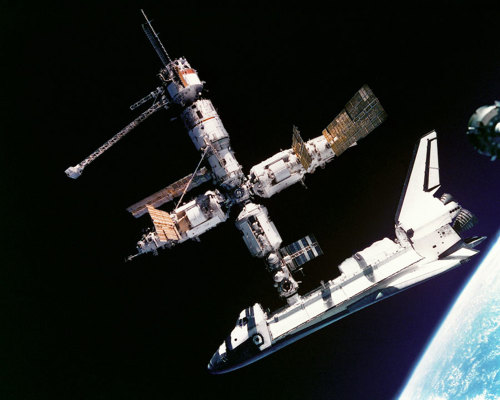

The cell receptors act like the dock on a space station. Imagine what would happen if the shuttle had a square dock and the space station had a circular one. The two wouldn’t hook up well and the astronauts would have a lot of trouble getting onto the space station.

This is exactly what happens with people who have a version of the CCR5 gene called delta 32. These folks have a circular dock. Now HIV has trouble injecting its RNA which slows down or even prevents it from infecting the cell.

This isn’t the only way to be resistant to HIV infection. Anything that keeps HIV from attaching to the cell will have a similar effect.

What I'll do for the rest of the answer is go over how HIV attaches itself to a cell. Then we can begin to understand how certain genes can keep that from happening.

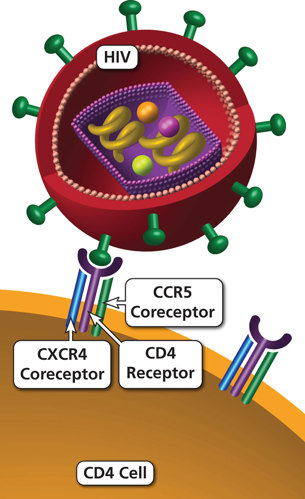

HIV Docking Station

The image below shows a cartoon of one way HIV attaches itself to cells. As you can see, the virus uses two separate receptors, CD4 and CCR5, to get a good grip.

The delta 32 version of the CCR5 gene makes no CCR5 receptor. What this means is that people who have this version of the gene make less CCR5 than normal. Or they make none at all.

So HIV has trouble getting a strong hold on one of these cells. And it has trouble infecting them as well.

Now losing a receptor isn’t always the best strategy for avoiding infection. After all, receptors are there for a reason and losing certain ones can have devastating effects.

For example, CD4 is critical in our bodies’ fight against infections. Not making CD4 would be a terrible way to be resistant to HIV. But CCR5 is a different story.

People don’t need CCR5 to live. In fact, there are many people (especially in Europe) who don’t make any of this receptor and are doing perfectly fine.

These folks are probably more susceptible to infection by the West Nile Virus (and maybe a few others) but they aren’t like the boy in the bubble.1 They aren’t ravaged by all the bacteria and viruses around them.

Stronger Resistance with Two copies of CCR5 Delta 32

As I said before, people who have the delta 32 version are more resistant to HIV infection. But not all of these people are equally resistant.

Remember, we have two copies of most of our genes – one from mom and one from dad. How resistant you are to HIV depends on how many copies of this version of the CCR5 gene you have.

People with one copy of the delta 32 version are somewhat resistant to HIV infection. This is because they still make some CCR5 receptors from their other “good” copy of the CCR5 gene. They have fewer docking stations which makes HIV’s job harder but not impossible.

People with two copies of the delta 32 version essentially don’t make any CCR5 receptor. They don’t have any good docking sites on their blood cells – only the CD4 receptor is there.

So these people have a circular dock which doesn’t match up well with HIV’s square one. They are more resistant to HIV infection because HIV can't attach itself very well to their cells.

Of course, HIV is an incredibly wily virus. Occasionally some virus still manages to get into these cells which is why even people with two copies of the delta 32 version are not totally immune.

More Than One Way to Skin a Virus

The delta 32 version of the CCR5 gene is found primarily in Europeans (click here to learn why).2 But other groups have resistant people too so there must be other genes involved. Scientists are working hard to figure out what these different genes are.

For example, one gene, CCL3L1, makes a protein that gets between HIV and the CCR5 receptor. Some scientists claim that a subset of resistant Africans has extra copies of this gene. Extra copies mean extra CCL3L1 protein. Which means there is more CCL3L1 to get in HIV's way.3

Scientists have found other genes that make people more or less resistant to HIV too. Finding these genes is important because they tell us about how HIV works. And if we know how it works, we can come up with new ways to block it.

For example, scientists are hard at work trying to come up with something that will keep HIV and CCR5 apart. Maybe something that can mimic what CCL3L1 is doing. No one would have thought of that approach without first finding out why some people are resistant.

Author: Dr. D. Barry Starr

Barry served as The Tech Geneticist from 2002-2018. He founded Ask-a-Geneticist, answered thousands of questions submitted by people from all around the world, and oversaw and edited all articles published during his tenure. AAG is part of the Stanford at The Tech program, which brings Stanford scientists to The Tech to answer questions for this site, as well as to run science activities with visitors at The Tech Interactive in downtown San Jose.

Skip Navigation

Skip Navigation